African American Cemeteries and the Restoration Movement

African American Burial Traditions

Africa is a heterogeneous continent with various religions, racial identities, and cultural practices. When slaves arrived in America, they came from different tribes. Once in America, slaves were deliberately separated from family members. Then implicitly and explicitly discouraged by their owners from expressing their cultural beliefs. One form of resistance to cultural assimilation was creating their own burial customs.

On plantations, funeral ceremonies usually occurred at night. Since slaves had to work all day, night was the only time for them to participate in the ceremony. But it also allowed neighboring slaves to commune across legalistic borders. This tradition continued into the 20th century. Pre-Civil War, slave owners, not wanting to use their arable land for slave burials, would bury slaves in hidden in remote spots among trees and underbrush. During the ceremony, attendees would perform prayers and sing hymnals. Some cemeteries have their headstones facing west for spiritual reasons. Some graves are marked with trees, plants (ex; Yucca) or wooden planks. Believing that since trees would continue after their burial, death would not be their end. By using temporary markers, the residents ensured that there would always be room in the cemetery for future generations. Once buried, slaves from coastal regions would surround the gravesite with shells to enclose the soul’s immortal presence. In other areas, offerings could be the last physical object the deceased touched.

Consequently, these traditions, along with the South's segregated past, has lead to the negative perception of Black cemeteries as being abandoned and unkept.

Preserving Black Cemeteries

In our capitalistic society, we have the tendency to focus on the most profitable options instead of the most humanistic. Landowners may ignore the existence of the cemetery or underestimate the size of the plot to support their building developments. Similarly, the University of Georgia had a recent issue, finding unidentified corpses in their construction zone.

However, most Black cemeteries were not delineated by deeds or legal instruments. Since cemeteries do not provide tax revenue for the county, disincentivizing the county from keeping up with the owners of the plots. Ultimately leaving the cemeteries forgotten by the local government. Once reintroduced to the cemeteries, counties have the legal right to choose whether or not to maintain ‘abandoned’ cemeteries. With that in mind, counties should be sure to include local Black communities in the decision making.

Some Black cemeteries do not have records of names, death certificate numbers or lists of relatives. Let alone a map of where people are buried. At Brooklyn Cemetery we are fortunate enough to have a record of names, death certificate numbers, spouse's name, and a map of the headstones in the cemetery. Arguably, the best way to understand demographic trends among early Black Americans is to exhume the bodies. However, not only is this method expensive, it’s intrusive. To decide whether it is best to use invasive research methods or not, counties should survey local Black communities. Commonly, communities prefer the cemeteries to be left alone. As we discussed earlier, even vegetation could have cultural significance.

All over the country, churches, associations and even city councilmen have taken to the Restoration Movement. People are realizing the value in preserving the African American history in those cemeteries and are working hard to do so.

Mount Olive Baptist Church in Glen Allen, WV has initiated cleanup in the Anderson Cemetery. Anderson Cemetery is a pre-Civil War cemetery that dates as far back as 1867. It was one of the first known burial grounds for slaves and African Americans in the area. It has been vacant and neglected since 1991 and after 25 years with the help of Baltimore Baptist Church, Mount Olive is going to restore it to a place of resting for those buried there. They hope that their efforts will beautify the location for family members to be able to come and celebrate the lives of their loved ones.

In McDowell County, NC, an association has been setup to aid in the restoration of 3 African American Cemeteries in and near Marion, NC inlcuding Glades and McDowell. The McDowell Cemetery Association Inc., which was formed in 2011, has been working with the City Councilman to get these cemeteries back to a condition of remembrance instead of deny. Through the help of the City Manager and City Councilman, they were able to get large amounts of help in the cleanup including prison work units, the McDowell Trails Association, Little & Lattimore Law Firm and other organizations. The Mcdowell Cemetery Association's restoration efforts became a city wide concern and hopefully it will continue as such.

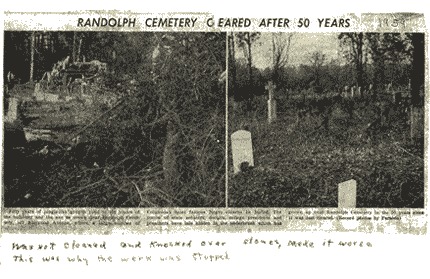

Randolph Cemetery in Columbia, SC served prominent black people starting from the Reconstruction era. The decline of Randolph Cemetery can be attributed to two factors. First, the cemetery ran out of plots in 1918. Second, during the Great Migration African Americans, including the descendants of those buried in the cemetery, left the south for more opportunities in the north. The cemetery was neglected until 1959 when the city was stopped from clearing out the cemetery by local, Minnie Simons Williams. From that moment on Mrs. Williams worked on preserving the cemetery by reforming the Randolph Cemetery Association. The association participated in a legal battle over the property, eventually earning the rights to the cemetery. In 1995, Randolph Cemetery won national recognition by being named a historical place. In 2006, the Downtown Cemetery Task Force secured state funding for landscaping, maintaining cultural customs and restoring grave markers and monuments.

In Portsmouth, Va four city-owned Black cemeteries; Mount Calvary, Mount Olive, Fisher’s and Potter’s Field Cemeteries, have been neglected since the 1960s. Efforts to preserve the cemeteries have met several stalemates, including its location. Before the creation of the cemeteries a creek ran through the area, creating common flood zones. Floodings are especially an issue when bodies float above the ground or stone heads become removed. Additionally, the close vicinity of I-264 to the cemeteries have created noise and light pollution. Fortunately, in 2010 the city of Portsmouth paid the Chicora Foundation to conduct research on the cemeteries to deduce methods that could best prevent further deterioration of the cemeteries.

Lastly, local citizens can preserve local black cemeteries through oral narratives, visiting the cemeteries, participating in clean-up efforts, being aware of ownership changes and being aware if fences or gates are built around the sites. If legal issues are surrounding the cemeteries, local organizations can coordinate law enforcement, medical examiners, and coroners to provide support for the preservation of the cemetery.

About four years ago in April of 2012, a group of UGA graduate students got together with one mission in mind, to help restore the Brooklyn Cemetery. They partnered with a local group that called themselves ‘Friends of Brooklyn Cemetery’ and these ten students along with UGA Professor Kathrine Melcher created a vision that would eventually highlight Brooklyn Cemetery as a unique Black Heritage Site. This group create a plan that included separating areas of the cemetery by building fences. Now, this could help identify certain families or graves based on what type of fencing encloses them. In addition, this could also protect some of the grave markers from environmental factors that erode them over time. The only question that plagued the group of students was what material will the fences be made of? This was a huge decision due to the fact that this cemetery has been overlooked in the past and the best idea would be to make the fences out of material that has a long life expectancy. One thing that was crucial to the success of this initiative was to have an action plan so they can make this dream a reality by giving the donors, sponsors, and potential granting agencies concrete ideas that their funds and time would go to. This was quickly turning into something that a community of people would soon get behind.

When you talk about restoration efforts and Brooklyn Cemetery you have to mention Friends of Brooklyn and their UGA liaison Linda Davis, they are the pioneers when it comes to humble service and restoration at Brooklyn. They now have a mission to raise money in efforts to build a fence surrounding Brooklyn to help make this cemetery a monument in the Athens Clarke County area.

I had the pleasure of interviewing Jennifer Hardister, Director of Community Outreach for ServeUGA, and the information she provided was simply amazing. ServeUGA, an organization founded about 4 and a half years ago, saw a need to restore such a monumental site such as Brooklyn. They saw that over the years’ evasive species started to take over and erode the grave sites until they were almost unrecognizable. ServeUGA’s main priority is to clear out the cemetery of unwanted species and ensure that each grave is recognizable and maintained over the years to come. Through a new program called Serve Athens, ServeUGA is increasing their efforts by partnering with Friends of Brooklyn Cemetery to serve twice a month at Brooklyn with hopes of restoring this historic site. Jennifer is definitely passionate about this cemetery and she love the rich history that many Athenians and residents of Athens don’t know about. She believes it’s imperative to make this a site that people want to preserve, want to visit, and more importantly want to celebrate. To help with these efforts please visit ServeUGA and Friends of Brooklyn Cemetery on Facebook and other social media. They say some volunteer get to taste the famous “Linda Davis Cakes.”

Works Cited

"Black History Dies In Neglected Southern Cemeteries." USA Today. January 30, 2013. Accessed October 20, 2016. http://www.usatoday.com/story/news/nation/2013/01/30/black-history-dies-in-southern-cemeteries/1877687/

"Bodies Being Removed From UGA's Baldwin Hall Parking Lot Aren't First to Be Moved From Site." Athens Banner-Herald. January 8, 2016. Accessed October 20, 2016.http://onlineathens.com/mobile/2016-01-08/bodies-being-removed-ugas-baldwin-hall-parking-lot-arent-first-be-moved-site

"Church Restoring Pre-Civil War African American Cemetery." - NBC12. N.p., n.d. Web. 29 Oct. 2016. http://www.nbc12.com/story/33094134/church-restoring-pre-civil-war-african-american-cemetery

"Decline of Randolph Cemetery." Historic Randolph Cemetery. 2010. Accessed November 4, 2016. http://historicrandolphcemetery.org/history/decline-of-randolph-cemetery.php

“Drainage Issues.” Chicora Foundation. 2010. Accessed November 5, 2016. http://chicora.org/pdfs/RC533%20-%20Portsmouth%20Part%202.pdf

"Forgotten graves: Silent cemeteries hold untold history." Athens Banner-Herald. March 8, 2004. Accessed October 20, 2016. http://onlineathens.com/stories/030804/new_20040308035.shtml#.WBOs4YWcHIU

Grave Matters: The Preservation of African American Cemeteries. Columbia, South Carolina. Chicora Foundation, 1996.

"History of Historic Preservation." New Georgia Encyclopedia. Last Edited October 17, 2016. Accessed October 20, 2016. http://www.georgiaencyclopedia.org/articles/arts-culture/history-historic-preservation

"Material Fabric." Historic Randolph Cemetery. 2010. Accessed November 4, 2016. http://historicrandolphcemetery.org/preservation/material-fabric.php

“Preservation of Mount Calvary, Mount Olive, Fisher’s and Potter’s Field Cemeteries.” Chicora Foundation. 2010. Accessed November 5, 2016. http://www.chicora.org/pdfs/RC533%20-%20Portsmouth%20%20Part%201.pdf

"The Committee For the Restoration and Beautification of Randolph Cemetery." Historic Randolph Cemetery. 2010. Accessed November 4, 2016. http://historicrandolphcemetery.org/history/crbrc.php