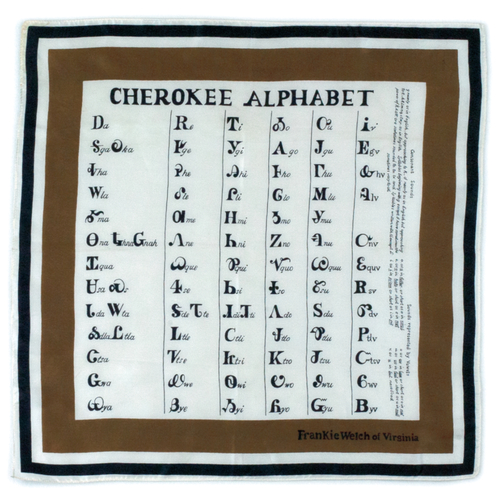

Cherokee Alphabet Scarf

In 1967, Virginia Rusk, wife of Secretary of State Dean Rusk, asked Frankie Welch to design something “truly American” for the White House and State Department to use as gifts. Inspired by the popularity of Yves Saint Laurent’s recent scarves and by a family trip to her hometown of Rome, Georgia, where she had seen an image of the Cherokee syllabary in a book of her father’s called History of Rome and Floyd County, she designed her Cherokee Alphabet scarf.

The Cherokee syllabary comprises eighty-four to eighty-six characters that represent syllables in the Cherokee language, rather than phonemes as in an alphabet. Sequoyah, an influential Cherokee born in Tennessee, created it around 1820 and is recognized as the only member of a nonliterate group to independently devise a successful system of writing.

The Cherokee Alphabet design was particularly meaningful to Welch, who enjoyed hearing family stories about having Cherokee ancestors. Though current genealogical research does not support the existence of a clear Cherokee connection in her family, she and her family and peers accepted the stories as fact. Welch hoped that her design would spark interest in, or at least awareness of, the Cherokee nation and donated a dollar from each sale to a scholarship fund she established for the higher education of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians.

On October 23, 1967, Frankie Welch introduced her Cherokee Alphabet scarf at the Athenaeum, home of the Northern Virginia Fine Arts Association, in Alexandria. Hote’ Casella, a mezzo-soprano whose father was Cherokee, played drums and chanted as models demonstrated various ways to wear the scarves. Among the models was the wife of the House minority leader from Michigan, Betty Ford.

Frankie Welch had the Cherokee Alphabet design reprinted at least forty-five times in a variety of colors on different fabrics, in slight modifications to the original design. She lined the walls of the entrance hall of her shop with 513 of the scarves. The Cherokee Alphabet design adapted well to clothing, and Welch used it for coat linings, dresses, bathing suits, and a custom uniform for a high school drum majorette. By June 1970 Welch offered Cherokee Alphabet short dresses and pantsuits in polyester for fifty or seventy-five dollars (about $340 or $505 today). For Welch, the design reflected this country’s history as well as her family’s history, and was an example of Americana.

With the success of her Cherokee Alphabet designs, Welch continued to include Native American-inspired elements in her work. By late 1971 she introduced a turtle design based on a piece of pottery found in Arizona. She also often used the turtle design, at least through the mid-1970s, as a logo with her signature. In 1973, Welch launched four additional Native American-inspired scarf designs (Thunderbird, Roadrunner, Basket Weave, and Squash Blossom), as well as new fashions, a line of jewelry, and a book titled Indian Jewelry.

In the book Welch discussed her experiences with Native American history and objects, gave tips on collecting, explained the meanings of select Native American motifs, and suggested ways to incorporate Native American jewelry into wardrobes and interior settings. A reviewer for Wassaja (a Native American newspaper) stated that Welch’s ideas about wearing Indian jewelry “would not be acceptable to most Indian women (and men)” but acknowledged her appreciation of and respect for Indian jewelry and deemed the book useful for “fashion-conscious [white] people who are learning to admire” and collect Native American jewelry.

Though today Welch’s Native American-inspired designs raise issues of cultural appropriation, a sensitive topic in contemporary fashion, she genuinely considered the designs as Americana and as reflective of her own family’s background. Prominent individuals of Indigenous heritage wore and enjoyed her designs, which increased their legitimacy. Welch’s designs were also in line with trends at the time, fitting a larger vogue for American Indian-inspired fashions in the late 1960s and early 1970s.