Division Plans & Development

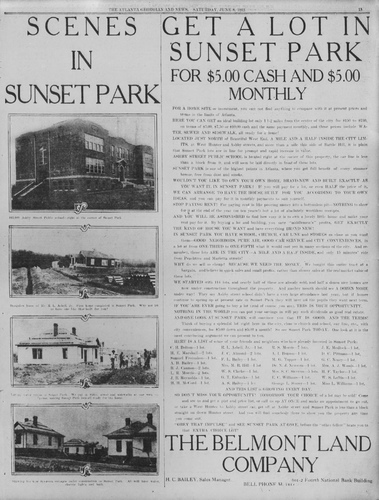

Before 1919 there were at least three plans for the development of a white neighborhood on the land that became known as Washington Park. There was an unnamed plan circa 1906; a 1912 plan named Sunset Park, which incorporated elements of the 1906 plan; and a 1914 plan named City View that was slightly altered in 1922 and renamed West Side Park. The construction of Atlanta University began to shift the demographics of the area, and as more Black residents moved into the neighborhood more white residents moved out.

The Black population in the area had already grown significantly by 1919 when construction began on the new park space. Once the Ashby Street School was redesignated for Black students, white developers abandoned plans for proposed neighborhoods, and Heman Perry began purchasing land in the area for a new residential development. By 1922, he had secured all previous drafted plans for development of the area. He used these, as well as one of his own, Washington Heights Terrace, to move forward with development of the property.

To further cement the area as a Black neighborhood, Perry sold some of his newly purchased land to the Atlanta Board of Education to fund the construction of a Black-designated high school. Along with Perry, members of the Neighborhood Union, a woman’s organization led by Lugenia Burns Hope, challenged the racism in the Atlanta public school system and pushed for better education of their children. In September of 1924, Booker T. Washington High School opened as Atlanta’s first Black High School for grades 7 through 10, with the two following grades set to be added as existing students advanced. The existence of two schools and a recreational area for Black citizens meant that Perry had great assets in play in order to create a unique neighborhood.

Perry’s many companies enabled him to manage the finance, construction, and insurance of residential buildings and other infrastructure needs of Washington Park. Perry himself lived in the district in the model home that he called the “Dream House” - an elaborate home showcasing what new life was available in this new community. As Perry and his companies developed the area, the population in west Atlanta swelled and the community flourished. Businesses from previously established Black areas of the city, such as Sweet Auburn, began to build important local buildings in the area, adding to cultural spaces already in place.

The Neighborhood Union worked to raise the standard of living in the community through programs focused on literary, musical, and arts education. The organization recruited teachers from Morehouse, Spelman, Atlanta University, and the Tuskegee Institute to offer classes ranging from cooking and embroidery to folk dancing and athletics. The Atlanta Chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People was also active in the community, connected through Lugenia Burns Hope who served as the first vice-president of the local branch. During her tenure, Hope oversaw the creation of citizenship schools which offered basic courses about the operations of the city, county, state, and national governments to foster the civic participation of Black voters. For almost 30 years, Lugenia Burns Hope served Black Atlantans and the Washington Park community, advocating for sanitary living and working conditions, better education, safe recreational activities, and improved medical and dental care.

The work of Perry, Hope, the women of Neighborhood Union, and the NAACP led to the greater opening of the westside to Black citizens and the improvement of living conditions for Black people in Atlanta.

As Perry and his companies developed the area, the population in west Atlanta swelled. Businesses from previously-established Black areas of the city, such as Sweet Auburn, began to build important local buildings in the area, adding to cultural spaces already in place. According to assessments of the community, “the opening of the Westside was the greatest single contribution to the improvement of living conditions in Atlanta for Negroes made in 25 years.”