Who is Buried in Brooklyn?

From the postbellum period through much of the twentieth century, Black Athenians comprised a diverse socioeconomic community, from laborers to doctors and educators. This section of our exhibit highlights individuals who appear in historical records such as archived newspapers or other public sources of information. In considering many of these accounts, it is critical to recognize the prejudice and negative bias of newspapers from the ninteenth and twentieth centuries that were employed against African Americans. By taking a closer look at the historical narratives of a few individuals buried in Brooklyn, we also consider issues facing the Black Athenian community as a whole.

Leah Towns

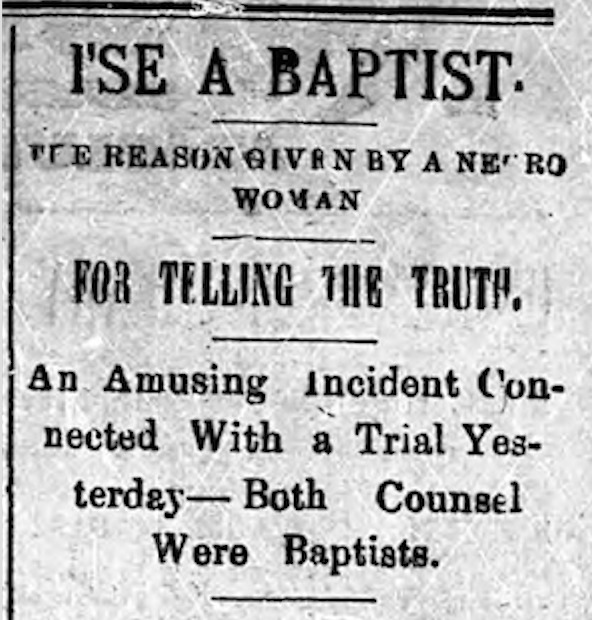

Leah Towns was an African-American woman born in 1858 to parents Sol Daugity and Julia Thacker. Based on her year of birth, she was most likely born into slavery and freed at about 7 years old. She was later married to Doc Towns, and they had a daughter named Ora Towns. She could not read or write, and she never attended school. Outside of these facts, there was little to be found about her day to day life. However, on September 27, 1895, an article titled “I’se A Baptist. The Reason Given By A Negro Woman For Telling The Truth. An Amusing Incident Connected With A Trial Yesterday--Both Counsel Were Baptists.” was published in The Weekly Banner, an Athens newspaper, about a trial of the State vs. Towns. Towns was being tried for assault and battery after allegedly getting into an argument with another black woman, Mary Sims, about stolen wood. The article provides a detailed outline of the case, with direct quotes from witnesses and members of the court provided. In summary, the crowd laughed throughout the trial as various African-Americans gave their testimonies, stating that they would never lie because they were Baptists, and Baptists do not lie. The jury included several prominent Baptist church members who decided in the end that Towns was not guilty, likely based on the fact that the jury “didn’t take kindly to the testimony of the witnesses for the prosecution”. Leah Towns’s story gives the reader a true taste of what life may have been like for an African-American in Athens immediately post-slavery. Although she was granted a trial, she and the other African-Americans involved were treated as inferior people to the crowd and the members of the court. At this point in Leah Towns’s life, slavery had ended, but her story shows how Black people were oftentimes still not treated entirely equally or with respect.

Arthur Massey

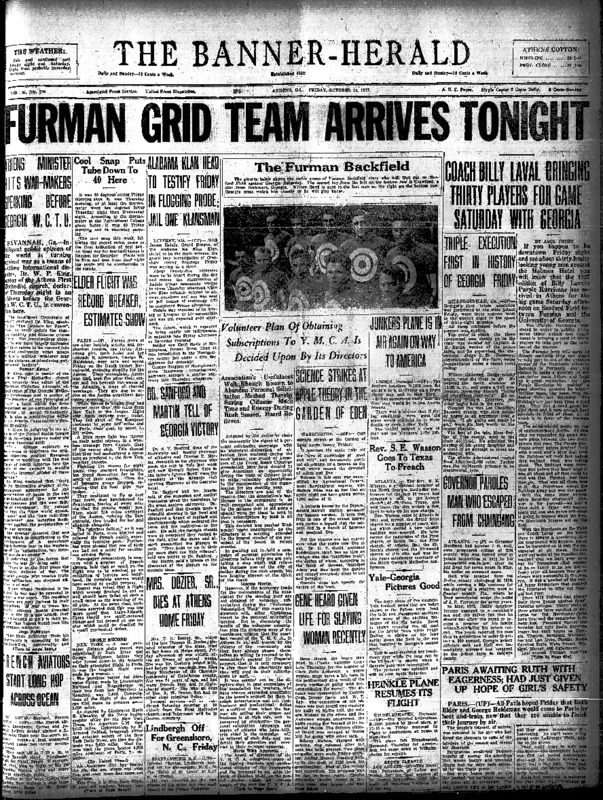

Arthur Massey was an African-American man who lived from 1902 to 1957. Although there isn’t much to be said about his basic information other than his age, gender, race, and location of residence -- Athens, Georgia -- a newspaper article and a court record gave some vague insights into what his life may have been like. On Friday, October 14, 1927, The Banner Herald published a column titled, “Gene Heard Given Life For Slaying Woman Recently”. The column gave brief descriptions of the most recent local crimes. It states that on that Friday morning, Arthur Massey pleaded guilty to the theft of $180 from his grandmother. It also states that part of the money was recovered, and his sentence was set for one to three years. This article is interesting because although it indicates to the reader that Massey was from then on considered to be a convicted man, it does not give any other context about the circumstances surrounding the situation. It is unclear if he stole the money with malicious intentions, or if perhaps he stole the money from his grandmother to purchase necessary resources for them. The brief nature of the column leaves the reader to come to his or her own conclusions about the situation in its entirety. However, 13 years later, on October 16, 1940, Massey was charged with the murder of Irene Taylor by shooting her with a pistol. After initially stating that Taylor was holding a knife at the time of the incident, he stated during his trial that Taylor did nothing to provoke the murder, and that he was “just fretted” (extremely anxious).

Ben Langston

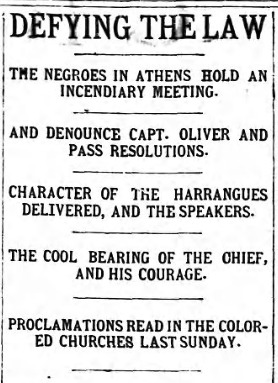

On a Monday night in late July of 1883, approximately 200 black people in Athens held a meeting in the Town Hall to protest and discuss resolutions for the nonfatal shooting of a black man named Jake Matthews by the white Chief of Police, Captain Oliver. Capt. Oliver shot this Mr. Matthews because he resisted arrest for allegedly stealing a cow from another man. This meeting was intended to denounce the actions of the Chief of Police, address the distrust between the black and white races, and to seek justice through a series of resolutions. With a derogatory and condescending tone, the newspaper denounces this meeting as a waste of time, declaring that “there are certain disorderly, lawless characters in our midst among the colored race that seem determined to stir up strife.” The newspaper dismisses the attendees of the meeting as “the laughing stock of the whole country.” This illustrates the newspaper’s negative bias towards black Athenians, and it shows the severity of the racial tensions underlying the Athens community during this time period.

Ben Langston, a black man buried in Brooklyn Cemetery, was an influential speaker at this gathering. He emphasized that their purpose as a group was to learn the truth; people must speak up if they knew something, regardless of intimidation by white men. He encouraged this by declaring himself afraid of no one, not “in earth or hell.” He told the gathering of people to “speak out like men, and if anything comes out of it I will be with you in six troubles and will not forsake you in seven.” These passionate words show the strong sense of injustice present in this gathering. Langston, a widower and father of Lula, worked as a drayman for Orr & Hunter. Born in 1861, he would have been about twenty-two years old at the time of this event. Showing courage and strength at such a young age, Langston is an impressive character whose story highlights the stark racial tensions in Athens during the late 19th century.

Janie King

Janie King, a laundress born in 1868, shows an another example of the negative newspaper coverage prevalent in old Athens. Mrs. King faced charges in 1914 for being an accessory to intended murder. Lula Bell was charged with alleged assault with intent to murder her husband, John Bell, and Mrs. King was accused of aiding and abetting her friend Ms. Bell by providing the gun used to shoot Mr. Bell. Mr. Bell was shot through the kitchen door, and although his injuries were critical, he recovered well after surgery. The only witness to this supposed event was the husband himself, and he could not testify against his wife in court. Therefore, there was no eyewitness account, and only circumstantial evidence could be used to in an attempt prove Mrs. Bell’s and Mrs. King’s alleged crimes. The final outcome of this case is unclear, but it shows the tendency of newspaper coverage to discuss black Athenians only in terms of their involvement with crime.

Private John H. Turman

Private John H. Turman served as a Light Weapons Infantryman and was a member of the 17th Infantry Regiment, and 7th Infantry Division. During the Korean War, the enemy seriously wounded him on August 28, 1951. He died of missile wounds the next day. His body was flown out of South Korea and was laid to rest in Brooklyn Cemetery in Athens. Private Turman was awarded the Purple Heart, the Combat Infantryman’s Badge, the Korean Service Medal, and the United Nations Service Medal. These awards were significant because black soldiers were traditionally not treated with the same respect as white soldiers. It is a great honor for a black man to have been given these prestigious awards.

Georgia Jones

Georgia Jones was born in 1851 and died Dec. 9, 1922, at the age of 71. Mrs. Jones was married to John Jones. The Athens Daily Herald reported on Oct. 26, 1914, that Mrs. Jones plead guilty to a charge of disorderly conduct in her house. However, the article reported that she said, “Innocent,” when charged with selling liquor during prohibition. According to the article, multiple witnesses swore she had sold them liquor, and others testified that she also previously gave away alcohol. However the article does not report an opportunity for Mrs. Jones to respond to those accusations. Mrs. Jones was found guilty and fined $125 for both charges. The article regarding the trial of Georgia Jones highlights the perpetual negative bias African Americans faced everyday in the early 1900s.

Ressie Bea Howell Smith

Ressie Bea Howell Smith was born July 15, 1914 in Crawfordville, Georgia, and died May 21, 1944 as a resident of Athens, Georgia. According to U.S. Census data, Mrs. Smith was married to Elijah S. Smith and living in Athens by 1940. She was a homemaker raising four children: Elijah Jr., Bobbie Lee, Lorenga, and Thomas. Interestingly, Ressie Bea’s sister, Beatrice also moved from Crawfordville, Georgia, to Athens, married a man with the last name of Smith, and is also buried in Brooklyn Cemetery. While there is not extensive information on the life of Ressie Bea Smith or her family, she is a prime example of the information available to historians researching Brooklyn Cemetery. The research often simply revealed the deceased’s family, occupation, level of education and home address; sometimes there was even less information to be found. However, researching these individuals is critical to unearthing the story of the early 20th century Athens. By combining the information of many with historical records similar to those of Ressie Bea Smith, historians can draw conclusions that represent the larger African-American community of Athens.

Along with the notable people buried in Brooklyn Cemetery that we have mentioned above, there were other individuals that we found with newspaper stories about them. We found people like Lizzie Byrd, a chambermaid who reported her son’s promotion in the Army, William Cobb, an owner of 200 acres of land, and Lucy Jones, a witness to a strange case. We hope this exhibit has given a closer look into some of the notable people buried in Brooklyn Cemetery and that it helps to paint a picture of what life was like for black Athenians.

Works Cited

"Bound Over On Assualt Charge." Athens Daily Herald. August 7, 1914. Accessed on October 4, 2016. http://athnewspapers.galileo.usg.edu/athnewspapers-j2k/view?docId=bookreader/ahd/ahd1914/ahd1914-1294.mets.xml;query=Janie%20King;brand=athnewspapers-j2k-brand#page/n0/mode/1up

"Defying the Law." The Banner-Watchman. July 24, 1883. Accessed on October 4, 2016. http://athnewspapers.galileo.usg.edu/athnewspapers-j2k/view?docId=bookreader/abw/abw1883/abw1883-0116.mets.xml;query=Ben%20Langston;brand=athnewspapers-j2k-brand#page/1/mode/1up

"Gene Heard Given Life For Slaying Woman Recently." The Banner Herald. October 14, 1927. Accessed on October 20, 2016. http://athnewspapers.galileo.usg.edu/athnewspapers-j2k/view?docId=bookreader/adb/adb1927/adb1927-2005.mets.xml;query=arthur%20massey;brand=athnewspapers-j2k-brand#page/1/mode/1up

“I’se A Baptist. The Reason Given By A Negro Woman For Telling The Truth. An Amusing Incident Connected With A Trial Yesterday--Both Counsel Were Baptists.” The Weekly Banner. September 27, 1895. Accessed on October 19, 2016. http://athnewspapers.galileo.usg.edu/athnewspapers-j2k/view?docId=bookreader/abw/abw1895/abw1895-0307.mets.xml;query=leah%20towns;brand=athnewspapers-j2k-brand#page/1/mode/1up

"One For Assault To Murder. The Other for Being Accessory." Athens Banner. August 7, 1914. Accessed on October 4, 2016. http://athnewspapers.galileo.usg.edu/athnewspapers-j2k/view?docId=bookreader/adb/adb1914/adb1914-1152.mets.xml;query=Janie%20King;brand=athnewspapers-j2k-brand#page/n0/mode/1up

"Police Break Up Tiger Near Depot." The Athens Daily Herald. October 26, 1914. Accessed on October 19, 2016. http://athnewspapers.galileo.usg.edu/athnewspapers-j2k/view?docId=bookreader/ahd/ahd1914/ahd1914-1855.mets.xml#page/1/mode/1up

Creators: Peri Levey, Sarah Nelson, Spenser Thompson, Frances Plunkett