Black Nationalism

Introduction

Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, the “traditional Civil Rights Movement” took place. For over a decade it dominated the black freedom struggle, operating under a strict philosophy of nonviolence with the aim of integrating facilities and expanding the rights of Black Americans. However, by the mid 1960s, years and years of nonviolent protest met with extreme and violent resistance, with what was sometimes considered marginal gains, was weighing on activists. Leaders like Malcolm X, Stokely Carmichael, and Huey P. Newton took the movement in a new direction: black power. Increased white resistance to SNCC activism in particular motivated many to believe that that nonviolence was a dated idea; subsequently many former SNCC activists (such as Carmichael and Kathleen Cleaver) left that organization to join black nationalist groups like the Black Panther Party. Furthermore, in a second Great Migration black people were migrating to cities in huge numbers, leading to urban chaos and its subsequent issues: exacerbated economic inequality, police brutality, and discrimination in healthcare and housing. The new movement, on the whole younger and more secular than the first, didn’t believe a nonviolent ideology could address those issues, and the others it found necessary for equality: police brutality, urban poverty, lack of access to healthcare and education and ingrained internal racism/a lack of black pride. It was usually secular, and it provided more opportunities for women to advance to leadership, yet had its own toxic gendered structures.

Birth of Black Power

Ideology of Black Nationalism

In order to understand the premise of the rallying cry Black Power, the ideology that gave birth to it, must first be discussed. Black Nationalism is an ongoing movement, which has existed long before the late 1960’s and early 1970’s. Early sentiments of Black Nationalism echoed throughout society as early as the 1920’s, when Marcus Garvey, founder of the Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA), called for black Americans to become completely separate from white society in a “Back to Africa” movement. In the less extreme case, Black Nationalism, is an ideology that is implemented through the phrase “black power”. In other words, Black Nationalism would be the mindset and black power would be the practice. In its simplest sense, black nationalists were in favor of racial pride among black people, economic self-sufficiency, and black separatism. The ideology itself was birthed out of Black Americans shared reality which has been shaped by oppressive systems created and maintained through slavery. It is a way to unite a people that has been displaced and striped from the very essence of their true identities. The ideology itself is a way for black people to understand who they despite being a part of a society that has used social forces as a way to subordinate them.

A few things to note about Black Nationalism that made it so appealing was its call for self-defense and separatism. With the creation of SNCC and their forms of protest through freedom rides and sit-ins, many black activists began noticing that as black people continued to push for their fundamental rights, white people began to push back, and white resistance became increasingly more violent than before. In other words, they truly believed that non-violence had seen its end. Embracing the notion of self-defense is not to be mistaken with senseless violence. It the implementation of the right to protect oneself not just against harm, but against oppressive systems, and barriers to racial equality. It is being dedicated to the cause of black liberation, and achieving it by any means necessary.

Black Nationalism also seeks to promote voluntary separation, whether through cultural, physical, or psychological means. In comparison to traditional civil rights leaders such as Martin Luther King Jr., Black Nationalists believed that the only way for Black Americans to understand their full potential in America is to become its own separate entity dependent on each other and not the government which seeks to oppress them. As a result, the notions of interracial activism as seen throughout SNCC, began diminishing. An embodiment of the notion of all black activism was seen when Stokely Carmichael became national chairman of SNCC in 1966. His first order of business, was to make it evident that white members would no longer be warmly accepted. Although argued by segregationists, and close-minded whites, in its essence, Black Nationalism was not an attack against white people, rather it was a way for black people to take control of their own fate, by whatever means they wished to employ.

Black Power is Born

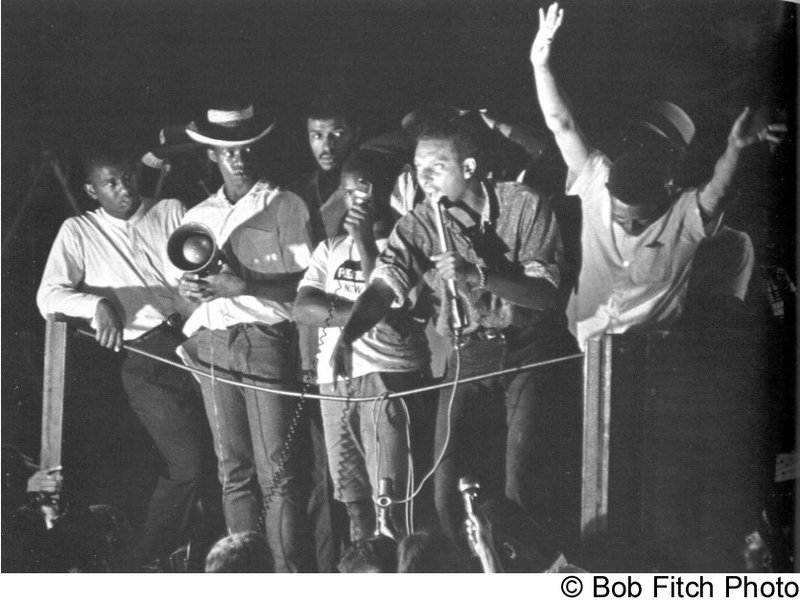

On June 5, 1966, James Meredith, who integrated the University of Mississippi four years prior, began a “March Against Fear” from Memphis, Tennessee to Jackson, Mississippi to encourage black voter registration. One day in, he was (not fatally) shot by a sniper. Martin Luther King, Jr. and Stokely Carmichael, among others, stepped in to continue his march. Ten days later, in Greenwood, Mississippi, Carmichael was arrested--his 27th time, he said--for pitching a tent on the grounds of a local black school. Upon his release he gave a rousing speech to a crowd of over 3,000, originating the phrase “Black Power.” “I ain’t going to jail no more… We been saying ‘Freedom’ for six years and we ain’t got nothin’. What we gonna start saying now is Black Power!” The crowd chanted “Black Power” back to him.

The march, shooting and speech were a turning point for Carmichael’s personal ideology as well as the Civil Rights Movement as a whole, from King’s nonviolent striving toward freedom to Carmichael’s emerging militant philosophy. Carmichael’s speech sent Mississippi whites into a flurry, prompting King to call the phrase “an unfortunate choice of words.” According to Meredith, the march and its aftermath “change(d) the whole direction” of the movement, saying in a recent interview, “‘Blacks were too scared to do anything, but they came out to greet James Meredith': That would have been the story in the evening news if I hadn't gotten myself shot. But I got shot and that allowed the movement protest thing to take over then and do their thing."

Black Panther Party

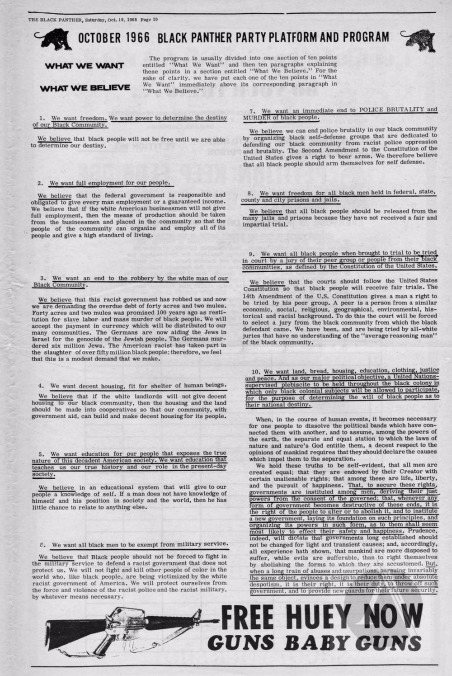

The Black Panther Party for Self Defense, founded in Oakland, California in 1966 by Huey P. Newton and Bobby Seale, sprung from resistance to police brutality (which was widespread against black and brown communities throughout the 60s). It ultimately morphed into a black nationalist group with a Marxist economic and humanitarian stance which held the belief that capitalism's oppression further subordinates black people. They were a militaristic group, exercising and fighting for their rights to carry weapons, but had many thoroughly humanitarian aims and programs. The Free Breakfast Program spread to every chapter in the country, and medical clinics, clothes and shoes drives, and legal aid were also prevalent in Panther chapters across the nation. After worldwide support and notoriety in its first decade ("Yellow Panther" organizations formed in Vietnam and the campaigns to free Angela Davis, Huey P. Newton, and others, receieved national attention), the Panthers faded in the late 70s and early 80s with many of its prominent members killed or exiled, often by the government, and mainstream public opinon swinging conservative.

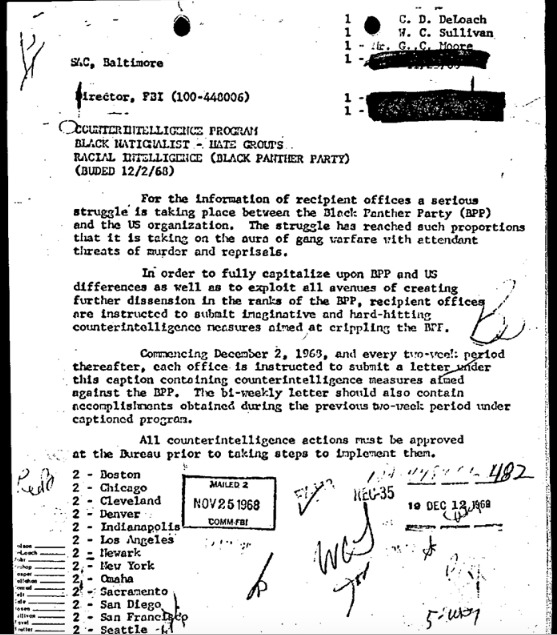

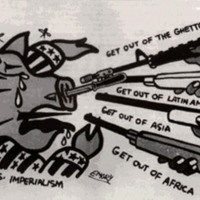

Resistance Against the Movement

With any form of protest against the status-quo comes resistance. As the black and brown liberation movements began to nationalize themselves, both the government and many white Americans began an intensive fight against their cause. The resistance often times not only became violent, but also deadly. As Black Nationalism and its rallying cry of black power became popular, it caught the attention of the FBI and was an easy target for white backlash. The FBI’s obsession with Black Nationalists and black liberation groups, was their political and social revolution through militancy and armed resistance. The FBI found its way into the movement through a program entitled COINTELPRO, or the Counterintelligence program, created in 1956. Initially, the program was designed to stop suspicious activities relating to communism. However, as Black Nationalism began making its mark across the nation, the FBI found a particular interest in the Black Panther Party. Through wiretapping, illegal surveillance, and other illegal methods to impede the first amendment rights of Black Panther activists, their tactics were simple: discredit the movement by arresting Black Panther activists on inflated crimes, which of course were politically motivated, branding them as leftist extremists and terrorists. The FBI painted the Black Panther Party as an organization seeking to overthrow the government through the use of violence. Black Panther members such as Angela Davis, Huey P. Newton and Bobby Seale were arrested on charges of murder, others were forced into exile, such as Assata Shakur, and some such as Huey P. Newton and Fred Hampton were brutally murdered. The FBI single-handedly destroyed the Black Panther Party, and succeeded at diminishing their role in society, to a simple “terrorist” group. The organization’s motives went beyond just “advocating” for violence. They dedicated themselves to the community, and even created a Free Breakfast Program to help children who were not able to eat before school. Although their tactics were scolded by the nation years later , the FBI succeeded in the takedown of the Black Panther Party’s prominent leaders, crumbling the organization, until it officially dismantled in 1982.

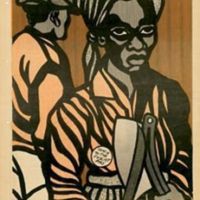

Aesthetics Shaping The Movement

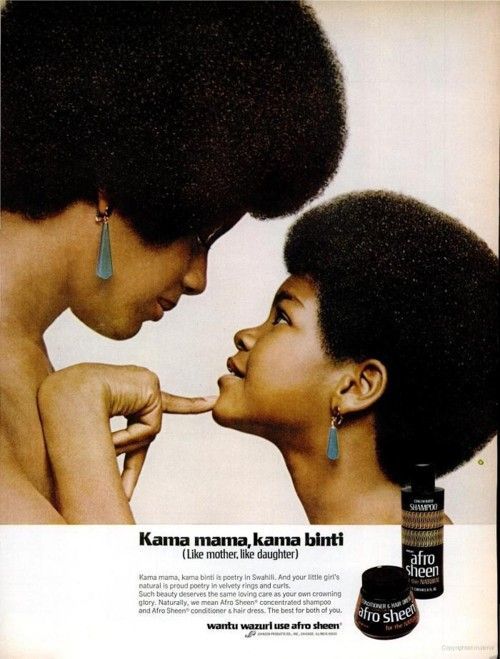

Cultural Nationalism played a major role within the Black liberation movement. It embodied more than just afros, shirts embroidered with the black power fist and speaking Swahili (chosen as the language of liberation). It served as a way for black people to gain a sense of pride in who they were. The idea of pride in oneself predates the 1970's era, when Marcus Garvey, a 19th century black activist, proclaimed “Black is Beautiful”. What made cultural nationalism valuable to the movement, was that many activist within believed that true liberation began with black people accepting themselves in their purest forms, separate from a white dominated society. It was a way for black people to see the beauty in themselves, when for so long, they were told their natural features were inferior. It gave them a sense of pride in being black. Cultural Nationalism in itself was a practice of black liberation. Black people were removing the “chains” of Eurocentric standards, and embracing their African roots. It allowed black people to articulate their own history and reality through their experiences, and not from the perspective of white people. It gave black people the power to create their own representation in the media.Black people were refusing to participate in their own subordination, by upholding themsleves to European standards. Although often times branded as unpatriotic of anti-white, cultural nationalism's sole purpose was to promote the ideology that many cultures can coexist within one society and not just one. It promotes the ideology that black people need refuge and safe places in what is familiar. It gave a voice to the voiceless, and a face to the invisible.

Angela Davis

August 7, 1970: the Marin shootout and the Free Angela movement

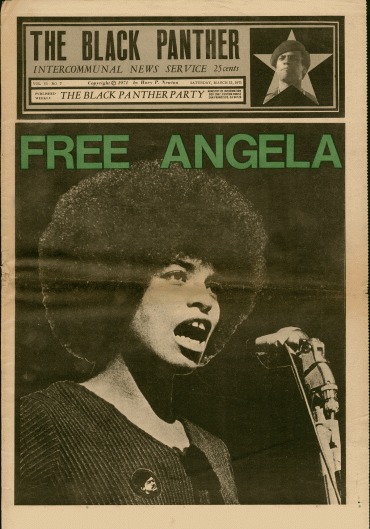

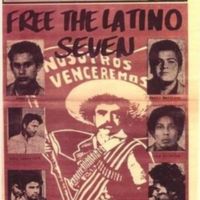

In college, Angela Davis joined the Black Panthers and an all-Black chapter of the Communist Party (which caused tension with both UCLA, the college where she later worked, and, later, the Reagan administration). When in 1970 three Black Panther Party members (known as the Soledad Brothers, though unrelated) were in court in Marin County, California after being accused of killing a guard in the Soledad Prison during a riot in which Black men were killed, an armed escape attempt was made during trial and people in the courtroom were killed. Immediately afterwards, Davis went "underground" and made the FBI's most-wanted list, the third woman ever to do so. While underground Davis garnered international support, with homes and organizations across the world declaring themselves safe houses for her. Caught two months later, on October 13th, Davis was charged with murder for her involvement in the shootout--she had owned the guns--and served 18 months in jail, during which time the Black Panther Party circulated literature such as this newsletter advocating Davis' acquittal. The campaign to acquit Davis was expansive: a New York Times article on the topic at the time claimed Davis "has an unprecedented political campaign being waged for her release all over the world. It is not to belittle the seriousness of her situation to say that she has the best-organized, most broad-based defense effort in the recent history of radical political trials--more potent than that afforded to any of the Panther leaders or the Chicago Seven."

Assata Shakur

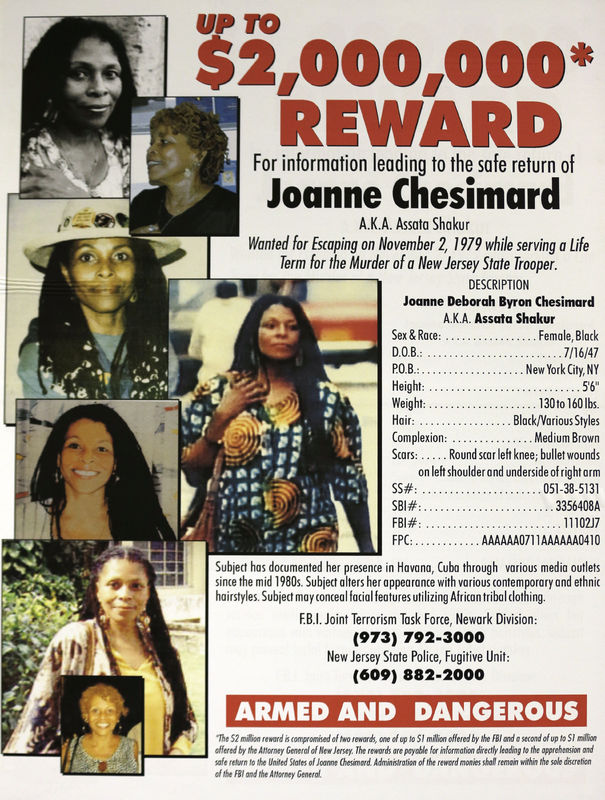

Assata Shakur, originally named Joanne Chesimard was a former Black Panther, and member of the Black Liberation Army. On May 2, 1973, Assata Shakur was accused of killing a New Jersey State Trooper. She was sentenced to life in prison, but escaped from jail on November 2, 1979, with the help of colleagues. She lived underground, and was eventually granted political asylum by Fidel Castro of Cuba, in 1984. Shakur, like other black revolutionaries was targeted for what society deemed as “radicalism”. Not only was she a victim of police harassment and brutality, but she suffered from sexism as well. It was one thing to be black, but it was another to be a woman. Shakur considered herself a black revolutionary because she believed in the fight against oppressive systems that subordinated all black people. Shakur understood that the government’s labeling of her, and other revolutionaries as terrorist was a way to brand the liberation movement as “…vicious, brutal, mad-dog criminals (Assata, pg. 50).” It was a way to frame revolution as anti-white and therefore anti-patriotic. Shakur, eventually became the first woman to be added to the FBI’s most wanted list, in 2013, and a subsequent bounty for her apprehension was set at $2 million. When we mention Black Nationalism and liberation, as seen with the traditional civil rights movement, we often times forget about the many women who dedicated their lives to the cause. Liberation is not something that can be reached by a subset of individuals within a marginalized group. More times than not, women are often marginalized within a marginalized community. Shakur embodied the essence of black liberation, all while challenging notions of what it not only means to be black in a white dominated society, but what it means to be a black woman, engaging in leadership activities usually reserved for men.

Elaine Brown

Elaine Brown was the first and only female leader of the Black Panther Party from 1974 to 1977. In the Party, she helped establish the first Free Breakfast Program and became editor of the Party newspaper Unilaterally appointed as chair by Huey P. Newton when he fled to Cuba, Brown admits she spent much of her time proving her own qualifications as leader in the existing "macho" power structure rather than making the Party more hospitable to women. Brown didn't support the ongoing wave of liberal feminism at the time because of its prioritization of advancing gender equality over racial equality, and its implied message that men hinder equality more than forces like capitalism. However she ultimately couldn't put up with the sexism in the Party, stepping down after male Panthers beat up a female member for reprimanding a male colleague, and Newton stood with the men.

Art and Literature of the Movement

The Black Nationalism movement, and the Black Panther Party in particular, continued the traditional Civil Rights Movement’s legacy of using Black newspapers as a tool of protest and organization. The BPP’s newspaper, The Black Panther, included news stories on BPP programs like the Free Breakfast program, updates on ongoing court battles, tributes to fallen members, in-depth articles on police abuses, and editorials weighing in on international battles, primarily supporting Castro and the Communists in Cuba.

Conclusion

As Black Nationalism spread, the nation bore witness to masses of black people moving away from the practice of non-violence. Black power was more than just a rallying cry, it proclaimed pride in blackness, when black people were constantly being told that blackness was subordinate to whiteness. It was a way for black people to express their indignations against the white power structure, token integration and reform, and unfulfilled promises of equality and justice. Although shaped as so by the media, Black Nationalism was not a movement to overthrow the government. It was a push to improve the government and enforce the due process clause of the 14th amendment that states all people should be protected equally under the law. Equality and freedom is not progressive nor will it be granted with time. The only way to strive toward a more egalitarian society is to fight for it. When the nation fought for freedom against the British government, it was called an American Revolution. When black people dared to speak for equality, it was called terrorism. The issue that most white people had with Black Nationalism was that for the first time, they would no longer be involved in the future outcome of the status of black people. It forced America to see the plight of black people as not just a social issue, but an American issue. Black people demanded their right to control their own lives, and the fear of having no power of Black Americans was too much to bear.

Bibliography

“Afrocentrism - Cultural and Political Movement”. Britannica. March 13, 2003. Accessed April 4, 2017. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Afrocentrism

Angela Davis on revolution and violence: Nora Ekard. “Angela Davis on Violence and Revolution”. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2HnDONDvJVE&t=88s. Chad Hurley, Steve Chen, Jawed Karim. July 26, 2015. Accessed March 31, 2017.

“At the Birth of Black Power.” Tufts Now. September 2, 2014. Accessed on April 1, 2017. http://now.tufts.edu/articles/birth-black-power

“Black Nationalism”. Britannica. July 1, 2008. Accessed April 4, 2017. https://www.britannica.com/event/black-nationalism

“Black Nationalism and the Call for Black Power”. Rcgd.isr.umich.edu. N/A. Accessed April 5, 2017. http://www.rcgd.isr.umich.edu/prba/perspectives/fall1999/asmallwood.pdf

“The Black Panther Party”. Alanna Birmingham Hidden Stories. N/A. Accessed April 5, 2017. http://alannabirminghamhiddenhistories.weebly.com/cointelpro.html

“Black Power-White Backlash: 150 Years of Struggle for National Liberation and Socialism”. Global Research. February 28, 2016. Accessed April 5, 2017. http://www.globalresearch.ca/black-power-white-backlash-150-years-of-struggle-for-national-liberation-and-socialism/5510800

“The Campaign to Free Angela Davis and Ruchell Magee.” The New York Times. June 27, 1971. Accessed on April 2, 2017. http://www.nytimes.com/books/98/03/08/home/davis-campaign.html/

CBS. “Black Power, White Backlash”. http://www.cbsnews.com/videos/black-power-white-backlash/?lumiereId=50034415&videoId=66d656c3-8bdf-11e2-9400-029118418759&cbsId=2906180&site=cbsnews. CBS. Peter Lang Publishing. June 8, 2007. Accessed April 5, 2017

“Celebrate the Anniversary of the Foundation of the Black Panther Party.” The Red Phoenix ALP. October 15, 2011. Accessed April 5, 2017. https://theredphoenixapl.org/2011/10/15/celebrate-the-anniversary-of-the-foundation-of-the-black-panther-party/

Cleaver, Kathleen Neal. “Women, Power, and Revolution.” New Political Science. Volume 21, Number 2, 1999. Accessed on April 2, 2017. http://proxy-remote.galib.uga.edu/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=a9h&AN=6673500&site=eds-live

“Cointelpro”. The FBI. N/A. Accessed April 5, 2017. https://vault.fbi.gov/cointel-pro

Digital Library of Georgia. “Afrocentric Education”. http://digitalcommons.auctr.edu/hilliard/31/. Galileo Initiative. February 11, 1991. Accessed April 4, 2017

“The Great Society and the Drive for Black Equality”. Digital History. 2016. Accessed April 1, 2017. http://www.digitalhistory.uh.edu/disp_textbook.cfm?smtid=2&psid=3329

“How the 1960’s Riots Hurt African-Americans”. The National Bureau of Economic Research. N/A. Accessed April 5, 2017. http://www.nber.org/digest/sep04/w10243.html

“James Meredith on What Today’s Activism is Missing.” Time. June 6, 2016. Accessed on April 1, 2017. http://time.com/4356404/james-meredith-50th-anniversary-march-against-fear/

“Los Siete de La Raza.” Ramparts. March, 1971. Accessed on March 4, 2017. http://www.itsabouttimebpp.com/Unity_Support/pdf/Los_Siete_de_la_Raza_Ramparts_1971.pdf

MALCOLMSREVENGE. “Malcolm X Kills Uncle Toms like A Beast”. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=93XHuPm9IUI. Chad Hurley, Steve Chen, Jawed Karim. August 24, 2015. Accessed March 31, 2017.

“Marcus Garvey and the Universal Negro Improvement Association”. Nationalhumanitiescenter. October 2000. Accessed April 5. 2017. http://nationalhumanitiescenter.org/tserve/twenty/tkeyinfo/garvey.htm

“Martin Luther King Jr. and the Global Freedom Struggle”. Kingencyclopedia.stanford. Accessed April 5, 2017. http://kingencyclopedia.stanford.edu/encyclopedia/encyclopedia/enc_black_nationalism/index.html

New Afrikan Independence Movement. “RBG – Why We Wear Our Hair Like This 1968, Kathleen Cleaver of BPP Breaks it Down.” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SUdHf6nqL9U. Chad Hurley, Steve Chen, Jawed Karim. October 1, 2012. Accessed March 31, 2017.

Ontiveros, Randy Jr. In the Spirit of a New People: the Cultural Politics of the Chicano Movement. New York City: New York University Press, 2014.

“The Panthers’ Revolutionary Feminism.” The New York Times. October 2, 2015. Accessed on April 2, 2017. https://www.nytimes.com/2015/10/04/movies/the-panthers-revolutionary-feminism.html

PBS. “Free Breakfast Program”. http://www.pbs.org/independentlens/videos/free-breakfast-program/. PBS. Independent Television. Accessed April 5, 2017

“Power Player.” Smithsonian Magazine. June, 2016. Accessed on April 1, 2017. http://proxy-remote.galib.uga.edu/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=fth&AN=115645679&site=eds-live#.WOUJxgj2UMQ.gmail

RetroBlackMedia. “Afro Sheen Ad 4.” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IrZ3c0x14TE. Chad Hurley, Steve Chen, Jawed Karim, September 20, 2010. Accessed April 4, 2017.

Shakur, A. (2014). Assata: an autobiography. London: Zed Books.

“Stokely Carmichael”. History. 2009. Accessed April 5, 2017. http://www.history.com/topics/black-history/stokely-carmichael

“This Day in History: James Meredith Shot.” History.com. 2010. Accessed on April 1, 2017. http://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/james-meredith-shot

“The Woman Question: Gender Dynamics within the Black Panther Party.” Spectrum: a journal on Black men. Fall, 2016. Accessed on April 2, 2017. https://muse-jhu-edu.proxy-remote.galib.uga.edu/article/634848/pdf

![black-panther_huey[1].jpg black-panther_huey[1].jpg](https://digilab.libs.uga.edu/exhibits/files/fullsize/c18606bc21506ce4c2d4440178122630.jpg)