Gay Liberation Movement

The history of the LGBT community has been met with its own unique set of challenges. This project looked at signifigant historical events in LGBT history, and focused specifically on student movements on college campuses such as the University of California at Berkeley, Columbia University, and the University of Georgia.

This timeline highlights signifigant historical events in the LGBT movement's history. This includes major events both on college campuses and within the general populous, as well as milestones in media representations.

Daily Californian

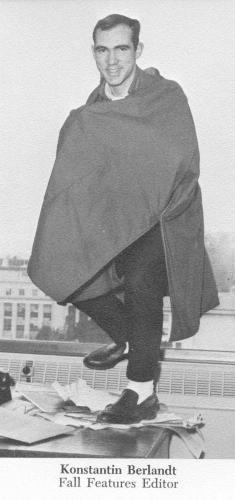

San Francisco was known to be one of the leading cities in the nation for gays, especially the University of California, Berkeley. There were over forty openly gay bars by 1960, and they had many customers that would go to them every day. The school newspaper, Daily Californian, decided to look into the gay activity that was happening on campus in 1965. Throughout November 29, 1965 and December 9, 1965 there was a series of articles that were published in the newspaper about “Sexual Minorities”, focusing on gay males. The features editor of the series in the newspaper was Konstantin Berlandt, who was an early gay activist known for pushing the limits of the university about gay liberation. The series begins with the headline “There are probably 2,700 homosexuals at Cal”, and it goes into detail about how police officers have been cracking down on the "homosexual activity" on campus, including removing every other door in the men’s restroom, so that it would stop people from drilling glory holes in the stalls. Then there are a series of personal stories by anonymous authors who speak about the gay activity that occurred on campus and in San Francisco at the time. The Publishers Board at the beginning of December wrote a statement that the series had “failed to meet accepted standards of journalistic ethics” (Daily Californian, 1965). The board took it back, because they were seeing a lot of backlash from people who supported the series and they agreed that it was a topic that needed to be talked about, so the series continued. Konstantin Berlandt allowed a conversation to be opened up about a controversial topic, and many people responded to it by putting their stories out there and allowing for the conversation to continue.

Students for Gay Power

In 1969, there were two student organizations that formed on campus, the Students for Gay Power and the Gay Liberation Front. The Gay Liberation Front was a political organization, and they focused their attention on the radical counter-culture to help fight discrimination against gays in “industry, the mass media, government, schools, and churches” (Gay Liberation Movement). During that Fall term, there would be the first of many protests calling for an end of police officers suppressing gay activity on the Berkeley campus. "The plaza in front of Harmon Gymnasium (now known as Spieker Plaza) was the site of the first gay liberation demonstration on the Berkeley campus. During the Fall Quarter of 1969 students picketed, calling for an end to the efforts of campus police to suppress homosexual activity within the environs of the gym" (Social Protest Collection). A number of safe spaces were created for gay students to be themselves. One of the main places was Sherwood Forest, and they were able to offer counseling, religious services, and a social coffee club on certain days of the week. The Students for Gay Power, ended up changing their name to the Gay Students Union in 1970, and they distanced themselves from the more radical Gay Liberation Front student organization.

The Gay Dance Ban

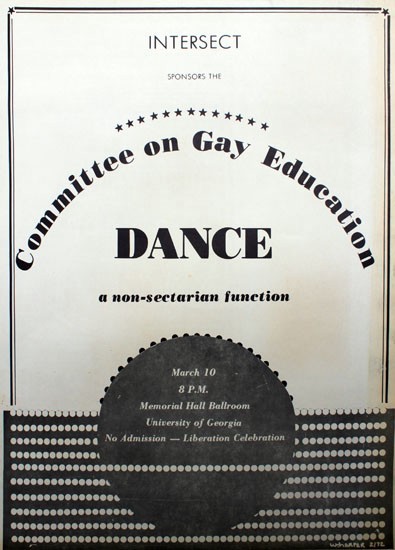

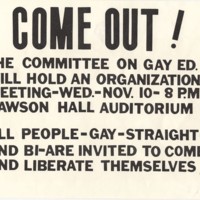

At the University of Georgia in the fall of 1971, inspired by the post-Stonewall organizing, John Hoard and Bill Green formed the Committee on Gay Education to spread awareness and educate about the gay lifestyle and homosexuality in general. However, the University refused to to recognize it as an official student organization as the administration, along with the university network, did not approve of its formation and purpose.

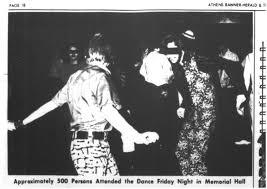

One of the first main objectives of the CGE was to hold a ‘Gay Dance’ to make themselves known and to gain recognition from the straight community and universtiy at large by showing them that gays really do exist. Intersect, an official student organization, secured the Memorial Hall Ballroom for the occasion because the CGE, having not received official recognition from the University, could not. However, trouble arose when the dance which was to be held March 10, 1972, was immediately cancelled by John Cox, the director of student activities, upon learning about it. In response to this, a group of about 35 students made up of CGE members led a march from Memorial Hall to the Dean of Student Affairs where they held a “sit-in” in protest of the ban put on their dance. During this sit-in the students developed a list of demands for the University which included: the University support the repeal of sodomy laws, the University provide facilities for the CGE, the University give permission to hold the gay dance as planned, and the University enforce the resignation of John Cox. However, despite the protest, Cox, along with the Dean of Student Affairs, Dean Sims, remained unyielding to the group’s cause. They justified their decision with the response that sodomy was illegal in Georgia, and the University could not and would not condone violations of the law that the dance would, in their opinion, inevitably lead to.

In response to this stance by the University, the CGE sought legal relief. On March 9, 1972, the day before the dance had been scheduled to take place, Bill Green and Rick Gilberg (the director of Intersect) filed an equality complaint accusing the University of denying them freedom of speech, association, privacy, and equal protection under the law and requested a temporary restraining order which would prevent the University from stopping the dance. The trial took place the next day, March 10, which was the same day the dance had been scheduled for. The result was the issuance of the restraining order allowing the CGE to proceed with the gay dance that very night just as they had originally intended.

Consciousness Raising

In addition to the great event that was the dance, the CGE hosted many consciousness raising events in the form of symposiums in hopes of exposing gays to their own oppression and to educate and raise awareness in the straight community about gays, their lifestyle, and the accompanying challenges. In 1973 the symposium, titled “The Corner of Your Room Can Be a Very Lonely Place” invited Jill Johnson, a noted feminist, as the keynote speaker. Her seminars intended to reflect on the lifestyles of gays in society and specifically in the workforce in hopes of educating gays about ways to improve their quality of life. Additionally, another symposium entitled, “Open the Door” was held May 16-18, 1973 and featured Barbara Gittings, a noted lesbian activist speaking on “Gay Lib: What Every Heterosexual Needs to Know.” The CGE hoped that this would give closeted gays a chance to blend into the expected crowd of heterosexuals and expose them to the problems people who are gay face in a heteronormative society while also exposing them to a supportive gay community. The CGE also designated a “Blue Jean Day” in which all gays and gay supporters were to wear blue jeans to show the university that gays do exist and do make up a considerable portion of the university population. While they did receive some clap back by groups such as Grad Studies who featured a poster reading “queer as a three dollar bill,” and there was an obvious decline in the number of people wearing blue jeans on campus as many people chose specifically to not wear them, the CGE reported the day as an overall success.

The Southeast Coalition

Additionally, the CGE sponsored the Southeast Regional Gay Coalition over the weekend of November 14, 1972 which delegates from over 16 gay activist organizations in the Southeast and members of the general gay population and gay supporter population attended. The coalition decided that their first goal would be to repeal state laws that were oppressive to people who are gay. The conference, held Friday, ended with a celebration dance held in the Memorial Ballroom with the entertainment provided by the band “Blue Max.” The president of CGE, Roy Wood, held the weekend to be a “great success."

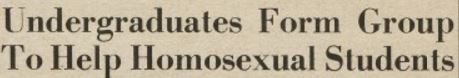

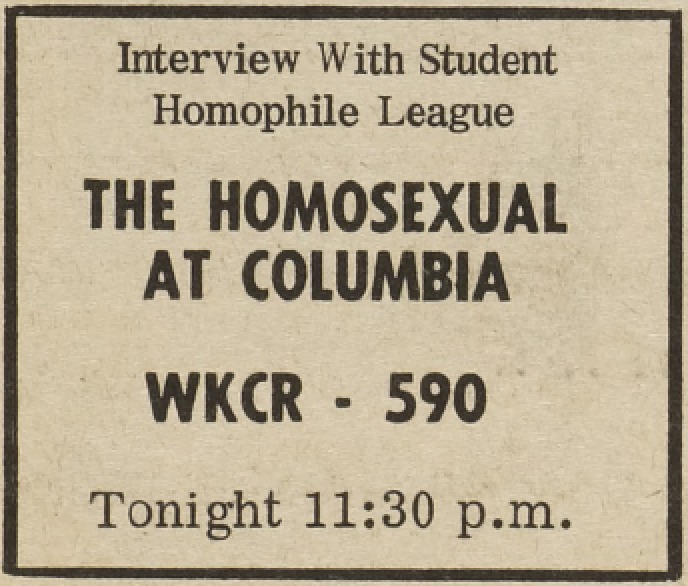

The Homophile League and Gay Liberation at Colombia

Gay Liberation at Columbia University came about without much resistance or criticism. The Student Homophile League, believed to be the first university supported organization for gay students, was founded at Columbia in 1966 and advertised their group in the student paper, the Columbia Daily Spectator. The group was founded to create a safe space on the Columbia campus for gay students to talk with others about problems they might be facing as gay students or just as students in general. The organization was open to people of all sexual orientation and was founded by an equal number of gay and straight students hoping to educate the campus about gay liberation, acceptance, and tolerance. The Civil Rights Movement acted as a precedent to the League for the equality they hoped to achieve on their campus and other campuses in New York.

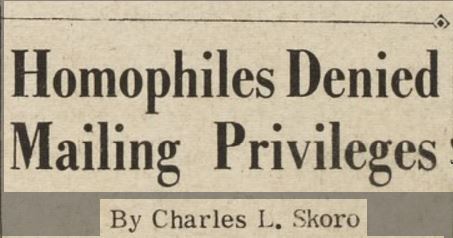

Most of the opposition the group faced was from adults working at the college. Anthony F. Phillip, the Director of Counseling Services, initially felt that the group was unnecessary and that issues gay students faced were problems faced by everyone on campus. His response was not so much against gays having an organization so much as he found the Student Homophile League to be purposeless and a waste of resources. The League did not just want to act as a counseling service though. They wanted to educate others about queer life and the stereotypes surrounding homosexuality. The group promoted guest lecturers who would come to Columbia to speak on homosexuality. Another authoritative opponent was the Dean of the college who denied the League the right to send a newsletter to incoming freshman and prospective students as all student organizations were permitted to do. The Dean did not want to advertise the gay presence on campus, so the League worked around his refusal. On September 29, 1967, the League made a statement in the Spectator declaring:

Those who feel themselves to be homosexual or bisexual or who are uncertain about their sexual orientation can expect sympathetic and confidential consideration from most of the religious counselors and the staff of the Columbia Counselling Service, as well as from the SHL [Student Homophile League] itself.

The group ended its declaration by adding, “We cannot at this time extend that statement to the College Dean's Office.” The League did not get to send their newsletter that year, but they made their presence known as an organization that would not be subdued and hidden in the shadows of other campus organizations.

Gay People at Columbia

Over the next five years, the Student Homophile League disappeared as a new organization took its place. Gay People at Columbia formed in the early-70s and worked to integrate school dances and provide gay lounges for students on campus. The Gay Activists Alliance was founded at the end of the 1960s in New York and was a national group rather than tied exclusively to Columbia, but many members of Gay People at Columbia were also members of the Gay Activists Alliance. In 1971, Morty Manford, president of Gay People at Columbia, fought vigilantly for a gay lounge in the unused basement of Furnald Hall insisting “Gay people need a place where they can get together unoppressed. They need a place where they can share their experiences as Gay people openly without fear of retribution.” The university’s president, William J. McGill responded to the Spectator that he didn’t believe Columbia was “obliged to give lounge space for the cultural activities of gay people” and felt he had to “draw the line” somewhere. Manford did get his lounge eventually and went on to fight for integrated school dances, a homosexuality studies department at Columbia, and for equal rights among gay professors.

Works Cited

"Herman E. Talmadge Collection, Subgroup C, Series XI: Flexys." Box 286, Folder 6: Richard B. Russell Library for Political Research and Studies, Date Accessed: March 28, 2017.

"Stonewall Timeline of Events." American Experience: PBS. Accessed Mar 22, 2017. http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/stonewall/

"Timeline: Gays in Pop Culture 1934 - 2010" Jennie Wood: Infoplease. Date Accessed March 16, 2017. https://www.infoplease.com/entertainment/timeline-gays-pop-culture-1934-2010

"Konstantin Berlandt." Gay Bears: Konstantin Berlandt. Accessed March 25, 2017. http://bancroft.berkeley.edu/collections/gaybears/berlandt/.

"Daily Californian, 1965." Gay Bears: Daily Californian, 1965. Accessed March 25, 2017. http://bancroft.berkeley.edu/collections/gaybears/dailycal/.

"Media Resources Center." Welcome to UC Berkeley Library. August 04, 2010. Accessed March 30, 2017. http://www.lib.berkeley.edu/MRC/pacificalgbt/pacificalgbt2.html.

"Gay Liberation Movement." Gay Bears: Gay Liberation Movement. Accessed March 29, 2017. http://bancroft.berkeley.edu/collections/gaybears/gaylib/.

“Gay Integration.” Columbia Daily Spectator. Feb. 18, 1971. Accessed Mar. 28, 2017. http://spectatorarchive.library.columbia.edu/cgi-bin/columbia?a=d&d=cs19710218-01.2.19&srpos=9&e=--1950---1972--en-20--1--txt-txIN-gay+-----#

“Why a Gay Lounge.” Columbia Daily Spectator. May 4, 1971. Accessed Mar. 29, 2017. http://spectatorarchive.library.columbia.edu/cgi-bin/columbia?a=d&d=cs19710504-01&e=-------en-20--1--txt-txIN------

“Columbia Homosexual Group Request a Gay Lounge.” Columbia Daily Spectator. Apr. 26, 1971. Accessed Mar. 24, 2017. http://spectatorarchive.library.columbia.edu/cgi-bin/columbia?a=d&d=cs19710426-01&e=-------en-20--1--txt-txIN------

“Homosexual Studies is Proposed.” Columbia Daily Spectator. Feb. 14, 1972. Accessed Mar. 23, 2017. http://spectatorarchive.library.columbia.edu/cgi-bin/columbia?a=d&d=cs19720214-01&e=-------en-20--1--txt-txIN------

“Letters to the Editor.” Columbia Daily Spectator. May 9, 1967. Accessed Mar. 21, 2017. http://spectatorarchive.library.columbia.edu/cgi-bin/columbia?a=d&d=cs19670509-01.2.20&srpos=3&e=--1950---1969--en-20--1--txt-txIN-homosexual-----#

“Undergraduates Form Group to Help Homosexual Students.” Columbia Daily Spectator. Apr. 27, 1967. Accessed Mar. 20, 2017. http://spectatorarchive.library.columbia.edu/cgi-bin/columbia?a=d&d=cs19670427-01&e=-------en-20--1--txt-txIN------

“Homophiles Denied Mailing Privileges.” Columbia Daily Spectator. Sept. 29, 1967. Accessed Mar. 21, 2017. http://spectatorarchive.library.columbia.edu/cgi-bin/columbia?a=d&d=cs19670929-01&e=-------en-20--1--txt-txIN------

“Program Announced for Gay Symposium.” The Red and Black. November 2, 1973. March 21, 2017. http://redandblack.libs.uga.edu/xtf/view?docId=news/1973/rab1973-0804.xml&query=program announced for gay symposium&brand=rab-brand

“Gays Form SE Coalition.” The Red and Black. November 14, 1972. March 21, 2017. http://redandblack.libs.uga.edu/xtf/view?docId=news/1972/rab1972-0800.xml&query=gays form se coalition&brand=rab-brand

“Blue Jean Day was Successful.” The Red and Black. April 18, 1978. March 24, 2017. http://redandblack.libs.uga.edu/xtf/view?docId=news/1978/rab1978-0386.xml&query=blue jean day was a successful&brand=rab-brand

“Gays Plan Dance, Forum.” The Red and Black. June 28, 1972. March 25, 2017. http://redandblack.libs.uga.edu/xtf/view?docId=news/1972/rab1972-0493.xml&query=gays plan dance forum&brand=rab-brand

“Lesbian Activist to Lead Workshop.” The Red and Black. May 11, 1973. March 22, 2017. http://redandblack.libs.uga.edu/xtf/view?docId=news/1973/rab1973-0452.xml&query=lesbian activist to lead workshop&brand=rab-brand

“Gays Protest Dance Ban Again.” The Red and Black. March 2, 1972. March 22, 2017. http://redandblack.libs.uga.edu/xtf/view?docId=news/1972/rab1972-0191.xml&query=gays protest dance ban&brand=rab-brand

“Student Homosexual Group Sues University for Million.” The Atlanta Constitution. November 11, 1972. March 27, 2017.http://search.proquest.com.proxy-remote.galib.uga.edu/hnpatlantaconstitution2/docview/1556827072/207DB2776E124120PQ/1?accountid=14537

“Athens Students Go To Court for ‘Gay’ Dance.” The Atlanta Constitution. March 5, 1972. March 27, 2017. http://search.proquest.com.proxy-remote.galib.uga.edu/hnpatlantaconstitution2/docview/1616010313/21BA67C012FE4D7EPQ/1?accountid=14537

"This gay dance in Georgia in 1972 changed the world." The Week - All you need to know about everything that matters. February 06, 2016. Accessed March 24, 2017. http://theweek.com/articles/603177/gay-dance-georgia-1972-changed-world.