What is Bioarchaeology?

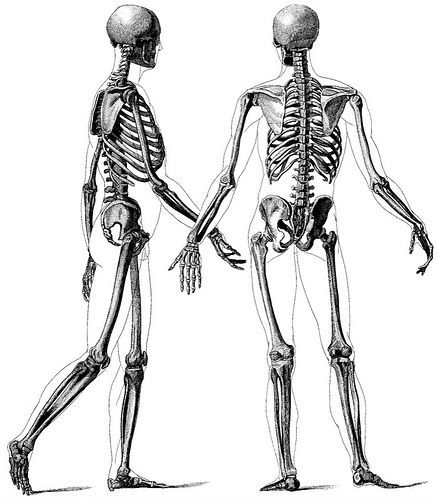

When most people think of the human skeleton, we think of a sturdy frame that gives support to our bodies. Sure, the skeleton grows during a person's lifetime, but once we reach adulthood, the skeleton appears to be fixed. In contrast, we tend to think of soft tissues, like muscles or fat, as the changeable and dynamic tissues of our bodies (think of a body builder, whose physique changes dramatically with working out). However, the skeleton is not just a rigid frame that is "fixed" once we reach adulthood: it is a biological tissue that can change during life, too, in response to our activity levels, nutrition, and disease. Some good examples are arthritis - a bony response to overuse of our joints - and osteoporosis - the result of insufficient calcium. Our skeletons are not the same throughout life: they change in ways that reflect aspects of our individual lived experiences.

Bioarchaeology is the study of human remains in archaeological contexts. Since it developed as an academic discipline starting in the 1970s, bioarchaeology has been a revolution in how we understand the lives of past human beings, because the study of human remains themselves frees the researcher of problems of historical bias. Information that would otherwise be invisible about humans’ lived experiences because it didn't make it into written records rises to the surface when the researcher consults the skeleton. In this sense, the skeleton provides some of the most direct evidence of past lived experiences.

Some of the methods bioarchaeologists use include the study of visible signs of infections and diseases on bones like porosities and new bone formation, arthritis, fractures and breaks, DNA analysis, cavities and abscesses in the teeth reflecting high-carb/high-sugar diets, stunting reflecting childhood malnutrition, bone geometric properties reflecting how active people were, microscopic scratches on tooth surfaces reflecting what people ate, and more.

What are Human Remains?

Human remains are unique among all other subjects of the archaeological record. Interpreted variously as kin, artifact, symbol, and more, the significance of human remains can vary among scholars, descendants, institutions, and across cultures and communities. Different stakeholders (people with an interest or concern in something) may have different perspectives on how to treat and study the skeleton, and how data are interpreted.

Given the multiple meanings of human remains to people across the world, there is no single prescription guiding treatment of human remains in archaeological contexts. The ethical codes relating to human remains research may not necessarily be prescribed procedural ethics, "the kind mandated by Institutional Review Board (IRB) committees" or in adherence to the law (Ellis, 2007). Rather, the ethics most pertinent to human remains are situational ethics, "the kind that deal with the unpredictable, often subtle, yet ethically important moments that come up in the field" (Ellis, 2007), and relational ethics. Regarding relational ethics, "there are no definitive rules or universal principles, as can be found in procedural ethics. Instead, relational ethics emphasizes that understanding the contextual details of the situation is critical to engaging in ethical behaviour, safeguarding the specific interests of all of those involved" (Zuckerman et al. 2014). Relational ethics requires people "to act from our hearts and minds, to acknowledge our interpersonal bonds to others, and initiate and maintain conversation" (Ellis, 2007: 4). Tackling this third dimension of ethics, which poses challenges in interpretation because of its fluidity and subjectivity, benefits from pursuit of contextual details in the form of historical research and engagement with descendants, and from updating approaches as necessary given changing circumstances. An example of the value of bringing descendant communities into work involving archaeological human remains can be seen in the Avondale Burial Place project, dubbed a Georgia Section 106 success story.

Guidelines and recommendations for treatment of human remains in archaeology have been outlined in a number of professional association, such as the American Association of Physical Anthropology (AAPA 2003 Code of Ethics). Anthropologist Phillip Walker argues that bioarchaeological projects should (1) treat human remains with dignity and respect, (2) give authority to descendent communities on the exhumation and reburial of the human remains, and (3) produce data that is valuable/important to contemporary populations. When it is possible for descendant communities to be identified, they should have a voice in the treatment of and knowledge about human remains, given that there is cross-cultural variation in how human remains are viewed and treated, and in whether or not the information gained is valuable.

Anthropologist Dr. Molly Zuckerman and colleagues (2014) have described how bioarchaeological research is important and warranted if we are to learn about people in the past, particularly underrepresented groups, such as enslaved individuals. They argue that applying the concept of embodiment (discussed in more detail below) provides an ethical imperative for the study of human remains – doing so provides a way to study the affects of power and oppression on the human body. The study of human remains can thus give a voice to people that were oppressed and marginalized and whose stories may otherwise be lost in history.

The Concept of Embodiment

Cultural and historical forces that shape our lived experiences – for example, what we eat, the stressors that we face, and the illnesses that we suffer from - literally become "embodied" in our hard and soft tissues. The concept of embodiment comes from epidemiological studies on negative health outcomes associated with social inequality in living populations. The concept is also applied to the study of human skeletal remains from past populations. As bioarchaeologists Agarwal and Glencross state, “the duality of the skeleton as both a biological and cultural entity has formed the basis of bioarchaeological theoretical inquiry.” Similarly, Rosemary Joyce asserts that the body is a “site of lived experience, a social body, and site of embodied agency.” These statements detail the human skeleton as contextually dependent; it is an embodiment of biological, cultural, and historical forces. In other words, the human skeleton is not just a biological entity, it is also shaped by cultural and historical processes, and the everyday lives of individuals

As outlined by Nancy Krieger, the human body can (1) tell stories about the condition of our existence; (2) tell stories that often, but not always, match people’s stated accounts; and (3) tell stories that people cannot and will not tell for various reasons. In other words, the human body can tell stories about our lives, even if they are not consciously expressed. Within this framework, skeletal remains can provide a unique window into the lived experiences of enslaved individuals in the United States, detailing how aspects of their lives, such as diet, health and activity patterns, were shaped under the United State's system of slavery. Examining bioarchaeological data in the context of historical accounts, such as slave narratives, can help us learn more about how slavery impacted diet, disease, and health.

The Bioarchaeology of Slavery

What we know about slave life in the United States has largely been drawn from written records and oral sources. Combined with these historical sources, bioarchaeology has provided new questions and perspectives related to the lived experiences of enslaved individuals, especially in regards to diet, health, and activity patterns. Bioarchaeological data from numerous plantations and cemeteries in the United States and Caribbean, such as the Newton Plantation in Barbados, the First African Baptist Church in the Philadelphia, the St. Peter Street Cemetery in New Orleans, Eaton’s Estate in North Carolina, and, most notably, the Avondale Burial Place in Georgia and the New York City African Burial Ground, illuminate how the slavery system was embodied in skeletal remains as indicated by poor diets, high stress loads, and negative health outcomes. Bioarchaeological data from post-emancipation cemeteries, such as Freedman’s Cemetery in Texas and Cedar Grove cemetery in Arkansas, show that African Americans continued to experience poor quality of life due to economic hardship and legalized discrimination.

The African Burial Ground in New York City provides an excellent example of how bioarchaeology can be used to reconstruct the lived experiences of enslaved individuals. The African Burial Ground project was directed by Dr. Michael Blakey, a professor at the College of William and Mary, director of the Institute for historical Biology, and a former president of the Association of Black Anthropologists (1987-1989). It was previously thought that the northern states were not active in the slavery system. However, bioarchaeological data from 408 individuals buried at the African Burial Ground (A.D. 1600-1794) show that enslaved people in New York work experienced increased disease burdens, low fertility, poor diets and arduous labor. As Blakey (1998) states, the work at the African Burial Ground provides a “vivid contrasting of a human face of slavery with its dehumanizing condition.” For more information on the African Burial Ground, please visit the National Park Service's website.

Over the past few decades, the involvement of African Americans, as both community voices and as scholars, has begun to transform the bioarchaeology of slavery. Within the discipline of anthropology, there is often a debate about who should participate in study the past and producing knowledge. As Blakey notes, “it is possible to work with communities and successfully struggle for a study of mutual interest to scholars and the public.” The New York African Burial Ground also provides an excellent example of how African Americans themselves can play a role in telling a history of slavery through bioarchaeological data. The project emerged as an interdisciplinary undertaking that emphasized critical race theory and engagement between scholars and the public. The project included 25 researchers at the Ph.D. level, public outreach, and an advisory committee consisting of African American activists that had input into the development of a research design and research questions.

References

Agarwal, S. C., & Glencross, B. A. (Eds.). (2011). Social bioarchaeology. John Wiley & Sons.

Blakey, ML. (1998). The New York African Burial Ground Project: An examination of enslaved lives, a construction of ancestral ties. Transforming anthropology, 7(1), 53-58.

Ellis, C. (2007). Telling Secrets, Revealing Lives: Relational Ethics in Research With Intimate Others. Qualitative Inquiry, 13, 3-29.

Joyce, R. A. (2005). Archaeology of the body. Annu. Rev. Anthropol., 34, 139-158.

Krieger, N. (2005). Embodiment: a conceptual glossary for epidemiology. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health, 59(5), 350-355.

Zuckerman, M. K., Kamnikar, K. R., & Mathena, S. A. (2014). Recovering the ‘body politic’: A relational ethics of meaning for bioarchaeology. Cambridge Archaeological Journal, 24(3), 513-522