Diet and Nutrition

Effects of Slavery on Diet and Nutrition: Examples of Resilience and Constraint

The narratives of enslaved Africans in the Federal Writers Project provide insight into what life was like during slavery. The people who were interviewed describe where they lived, what they did during the day, and sometimes give detailed accounts of what they ate. This section highlights some of the stories surrounding food and nutrition from formerly enslaved people from Athens, GA.

At the time of his interview for the Federal Writers Project, Elisha Doc Garey was 76 years old. He was born in Hart County to Sarah Anne Garey and had four brothers (John, Lindsay, David, and Joseph), a sister, Rachel, and a half-sister, Sallie. When asked about what he ate he explains:

"Anything I could git. Peas, green corn, 'tatoes, cornbread, meat and lye hominy was what dey give us more dan anything"

Many of the interviews from the Slave Narratives talked about cornbread, biscuits, and other starchy, sticky foods. Dosia Harris, from Greene County, even describes "good old ginger-cakes made wid sorghum syrup.” This likely would have caused many cavities, so we expected high rates of dental caries and abscessing in the individuals from the cemetery.

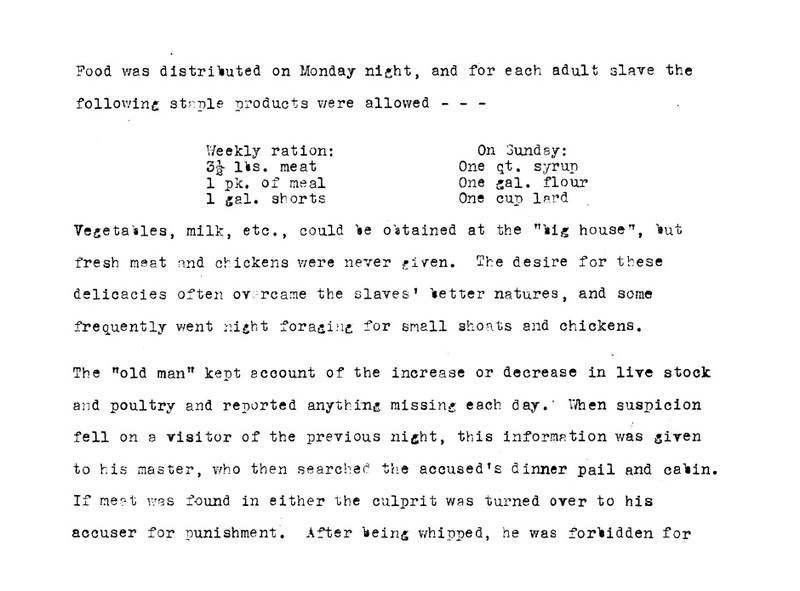

Enslaved Africans also seemed to have access to gardens with corn, collard greens, peas, and other vegetables, and many of the plantations had hogs that provided meat for both the white family and the enslaved families. Other sources of meat included possums, rabbits, and fish.

Alice Green: "Us had all de 'possums, squirrels, rabbits, and fish us wanted cause our marster let de mens go huntin' and fishin' lots"

Dosia Harris: "Slaves would wuk all day and fish all night"

What can bioarchaeology tell us about diet and nutrition?

Historical records and newspapers can tell us a lot about diet in the past, but it can sometimes be more focused on certain groups of people, especially the wealthier people who could afford people to write about them. Bioarchaeology can tell us about the people who may not have been written about while they were alive and is a valuable resource when recreating the experiences of enslaved people living in Athens. Additionally, bioarchaeology can provide direct evidence of what people consumed. Certain foods are more likely to cause tooth decay, such as sticky carbs like cornbread. Other diets can cause dietary deficiencies is they don't have all the nutrients you need. Follow the link below to learn more about what bioarchaeologists use to study diet and nutrition in the past.

What are we collecting?

Oral health: Dental Caries, Abscessing, Premortem Tooth Loss

Dentition can be a useful tool in trying to understand the life of individuals because oral health often reflects overall health and certain criteria within dentition can be used to estimate dietary lifestyle choices and nutrition. One thing we will be analyzing is the presence of dental caries in an individual. Dental Caries is a disease process that causes eroding of tooth enamel; the protective mineral substance found covering a tooth (Hillson 2001). The decay then leaves a hole, or cavity, on the tooth. Because decay occurs when bacteria from fermented carbohydrates (especially sugar) is produced, the likelihood of developing a cavity increases with eating more carbohydrates such as corn and wheat (White and Folkens 2005). We will also be analyzing Abscesses, which are pus-filled cavities formed near tooth roots when tissue disintegrates from infection. When the area around a tooth becomes too abscessed, Premortem Tooth Loss can occur where the tooth falls out and the surrounding bone in the jaw is taken away, creating a smooth surface where the tooth used to be.

Dietary deficiencies

While we are examining the skeletal remains of individuals from the Old Athens Cemetery, we pay close attention to any signs of dietary deficiencies. Dietary deficiencies can cause certain symptoms, which can cause damage to the skeleton. Some of the diseases that we look for include scurvy and rickets. Scurvy is caused by vitamin-C deficiency and it can create many tiny holes in areas close to chewing muscles, such as the roof of the mouth and the jaw (Ortner 2001). Fruits and vegetables are a good source of vitamin-C. Rickets is commonly caused by vitamin-D deficiency. A person who has rickets will have soft and semi-flexible bones, causing them to become curved (Larsen 2015). We get vitamin-D from fortified milk and some moderate sun exposure, but back then the only way to get vitamin-D was going outside. If we find some of these pathologies among the individuals buried in the Old Athens Cemetery, it may show that they did not have a sufficient diet; perhaps due to poverty and social status, famine, or other possible causes. In this case, the disease scurvy could be caused by a shortage of fruits rich in vitamin-C. Since Georgia relied predominantly on agriculture to stimulate its economy during the 19th century and throughout the state’s history, droughts were particularly severe in their impact. They could result in both economic downturns and food shortages throughout the state, but particularly in isolated rural communities.

Dental wear and dental microwear

Throughout each of our lives we are almost constantly using our teeth. The actions of chewing, biting down etc., which are most associated with eating, leave behind wear and tear on teeth. Luckily for osteologists, the patterns of wear on teeth can be seen even after a person dies as signs of what that individual was consuming when they were living. Dental wear is useful for estimating the age of a person because extensive use of your teeth over time wears down the tooth surface. Additionally, osteologists use dental microwear to study the occlusal surface (top) of teeth, where streaks and pits are made from the food people eat (Schmidt 2001). Streaks are lines across the tooth crown surface that is usually indicative of softer foods. The pits come from harder foods such as nuts, seeds etc. Therefore, someone who ate more nuts, roots, or seeds may have more pits than streaks on their teeth. Other activities also create marks and pits that mimic patterns made by food, so it can be a challenge to interpret diet. For example, preparation of food, such as using stones to grind corn that leaves tiny pieces of grit, may leave different marks. These diagnostic signs will be used to study the Baldwin Hall collection and identify how individuals likely used their teeth.

Linear enamel hypoplasias

Linear enamel hypoplasias (LEH) are deep grooves across the enamel of your teeth (Larsen 2015). They are caused by both specific and general stress and are useful in understanding dietary strain on groups of people. We record how many teeth have these deep grooves. Because teeth form early in childhood, observing patterns of linear enamel hypoplasias tells us about how stressful a person’s life might have been when they were younger. Bioarchaeologists often use linear enamel hypoplasias to understand if people had good lives with enough food, or if people were stressed as children. Analyzing LEH in the individuals uncovered from the Old Athens Cemetery can lead to many fascinating and exciting insights into the real life of the regular people who lived in Athens during the early to mid-1800`s. The prevalence of LEH on the teeth of these found can give researchers an idea of the burdens of life during that time period. For example, if there were a high number of individuals with LEH found on their teeth it could be an indication of inability to acquire food or another major stress like an epidemic. Unlike with most written accounts of the time, which mainly deal with the lives of the upper classes of society; examining the evidence left behind on teeth and bones of people who lived during this time period fill in the blanks of history books.

Comparing Our Data

Once we've collected all our data, we have to compare it to other data from the US from similar time periods. We compared data at several sites.

The links below present the results from our research on oral health, malnutrition, and growth at the cemetery.

For more information on diet and nutrition in the past or the comparative populations, here are the sources we found very interesting and useful:

Anon. 1825. Macon-Knoxville Store Ledger, 1825-1831. Athens, GA: Digital Library of Georgia, 2014.

Anon. 1832. Various Advertisements from Southern Banner. Athens, GA: Digital Library of Georgia, 2014

Buzon MR, Walker PL, Verhagen FD, Kerr SL. 2005. Health and disease in nineteenth-century San Francisco: Skeletal evidence from a forgotten cemetery. Historical Archaeology 39(2): 1-15.

Davidson JM, Black R. 2015. The confederate and the freedmen: bioarchaeological comparisons from the Reconstruction-era South. Southeastern Archaeology, 34(1): 1-22.

Graham L. 2014. A bioarchaeological comparison of oral health at three Postbellum African American cemeteries in coastal and central Georgia. Thesis, Georgia State University, 2014.

Higgins RL, Haines MR, Walsh L, Sirianni JE. 2002. The poor in the mid-nineteenth-century northeastern United States: Evidence from the Monroe County Almshouse, Rochester New York. In Steckel RH, Rose JC, eds. The backbone of history: Health and nutrition in the western hemisphere. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 162-184.

Hillson S. 2001. Recording dental caries in archaeological human remains. International Journal of Osteoarchaeology 11(4):249-289.

Hull AL. 1906. Annals of Athens, 1801-1901. Athens: Banner Job Office. pp 544.

Inscoe, John C. "Georgia in 1860." New Georgia Encyclopedia. 03 August 2016. Web. 13 September 2016

Larsen CS. 2015. Bioarchaeology: Interpreting behavior from the human skeleton. Cambridge: University of Cambridge Press.

Marshall C, Warren M, Doster G. 2016. Personal communication in Osteology. September 26 2016.

Ortner DJ, Butler W, Cafarella J, Milligan L. 2001. Evidence of probable scurvy in subadults form archaeological sites in North America. American Journal of Physical Anthropology 114:343-351.

Rose JC, Santeford LG. 1985. Cedar Grove Burial interpretation. In Rose JC, ed. Gone to a better land: A biohistory of a rural black cemetery in Post-Reconstruction South. Fayetteville: Arkansas Archaeological Survey. Pp. 130-145.

Saunders S, DeVito C, Katzenberg MA. 1997. Dental caries in nineteeth-century Upper Canada. Am J Phys Anthropol. 104:71-87.

Schmidt CW. 2001. Dental microwear evidence for a dietary shift between two nonmaize-reliant prehistoric human populations from Indiana. Am J Phys Anthropol 114(2):139-145

Steckel RH, Larsen CS, Sciulli PW, Walker PL. 2005. Data collection codebook. The global history of health project. Columbus: Ohio State University

Sutter R. 1995. Dental pathologies among inmates of the Manroe County Poorhouse. In Grauer A, ed. Bodies of evidence: Reconstructing history through skeletal analysis. New York: Wiley-Liss. Pp. 185-196.

Tigner-Wise L. 1989. Skeletal analysis of a Mormon Pioneer population from Salt Lake Valley, Utah. Master’s thesis, Department of Anthropology, University of Wyoming, Laramie, WY.

Wesolowsky AB. 1991. The osteology of the Uxbridge paupers. In Wesolowsky AB, Elia J, eds. Archaeological excavations at the Uxbridge Almshouse Burial Ground in Uxbridge, Massachusetts. Oxford: Tempus Repartatum. Pp 230-253.

White TD, Folkens PA. 2005. Human bone manual. Academic Press.