A Brief History of the U.S. Navy Pre-Flight School at UGA

Very shortly after the United States was launched into World War II on December 7, 1941, a delegation from the U.S. Navy arrived on the campus of the University of Georgia campus in Athens. Their task, in the chill of that late December, was to ascertain whether or not the University would be a good site for one of several planned Pre-Flight Schools being spun up for the Navy’s aviation contribution to the war.

Though there was an early indication that the Pre-Flight program might end up in Atlanta at Georgia Tech (already the site of a Navy R.O.T.C. program), by February of 1942, UGA alumni Richard Russell and Carl Vinson reassured University officials that Athens would indeed be the home for the program. This contract was signed on March 19, 1942 (NOd3035).

This decision was in part influenced by the success of the S.A.T.C. (Student Army Training Corps) program in Athens during World War I. In addition, the University had been working with Clarke County and the Civilian Aeronautics Administration since 1939 on a pilot training program, which was recognized as the University of Georgia School of Aviation in 1941 (headed up by Dean William Tate).

The University was home to one of four such programs initially. Pre-Flight Schools were also located at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, the University of Iowa in Iowa City, and at St. Mary’s College in Moraga, California. At all of these institutions, it was recognized that the infusion of men and money for the war effort would help offset declining regular classes due to the enlistment of college men in the fight.

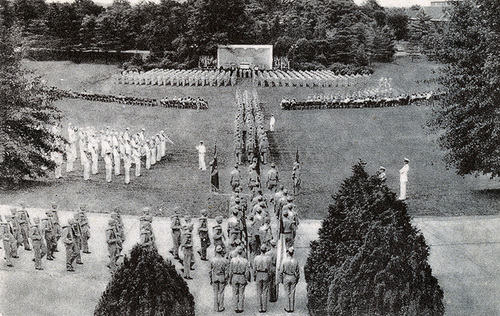

The ceremony opening the Pre-Flight School in Athens took place on June 18, 1942, took place in Sanford Stadium, and saw about 3,000 in attendance. The dignitaries included the head of the Athens Pre-Flight School, Charles E. “Skipper” Smith (he would serve all four years of the school’s operation). Included in the on-field display were the 242 men of the first Athens Pre-Flight battalion, who presented arms, and formed a giant block “NAVY” on the field for all to see. University of Georgia President Harmon Caldwell reassured the crowd that the University would comfortably manage both its regular mission of educating the youth of the state (and beyond) and its new mission of wartime support.

Logistically, the plan was for 2,000 cadets to be in training at any one time in the program, in addition to a like number of regular college students. The program was treated as a ship, with an ideal complement of 336 staff members (69 for administration; 93 for athletic programs; 108 for academics, and 64 for purely military functions). The ‘ship’ in Athens had a staff which fluctuated between 200 and 338, with members of the WAVES (Women Accepted for Voluntary Emergency Service) and the U.S. Marine Corps numbered among the instructors.

Among the instructors, there was a young coach from Vanderbilt, Paul “Bear” Bryant, who would serve at Athens, see wartime action in North Africa, and move on to the Pre-Flight Program at Chapel Hill during the war.

The physical plant of the University was placed at the service of the Pre-Flight program. The demonstration classroom building was converted into an administration building, and seven dormitories were transferred to Navy control.

For the duration of the program, former halls Old College, Candler, Brown and Milledge were known as Ranger, Yorktown, Hornet, and Wasp Barracks respectively.

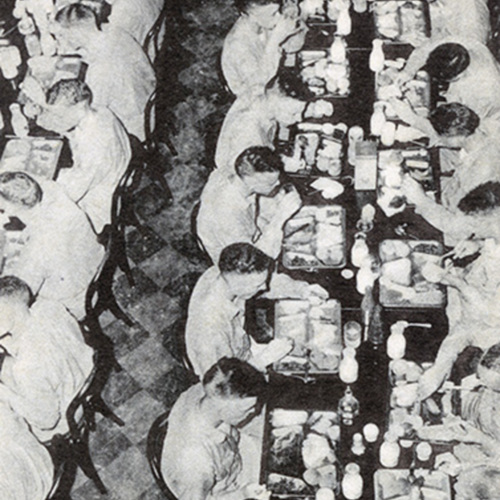

A total of 32 University structures were used by the Navy. The former Snelling Hall became the john Paul Jones Mess Hall, and Connor Hall was used for the showing of training films and a ship’s store. The Agronomy Barn was converted to a field house, and the other athletic facilities were made available to the cadets. There was a recreation center established on the third floor of Memorial Hall.

The Navy also engaged in additional construction, placing an indoor drill and training facility and swimming pool (Dahlgren Hall) in the central campus, and built an additional 3 barracks facilities (Essex, Saratoga, and Bon homme Richard) on south campus.

The school also had facilities off the UGA campus, including an extensive series of Victory Garden plots out beyond the Coordinate College campus on Prince Avenue, and an officers’ club which was located at the Athens Country Club.

The school was on the U.S.O. circuit, and entertainers like Bob Hope (in 1943), Jack Teagarden, and Pat Hudspeth were welcome enhancements to the school’s 49-piece band (the band in Athens was distinctive in that it was the only band among the Pre-Flight schools not to be composed exclusively of all-black servicemen).

As part of the school’s public relations mission, the local school’s Skycracker first began its weekly appearances in February of 1943. This publication kept the cadets up to date on the other pre-flight schools as well as the day-to-day goings-on at the Athens facility. The average print run of Skycracker was 3,000 copies.

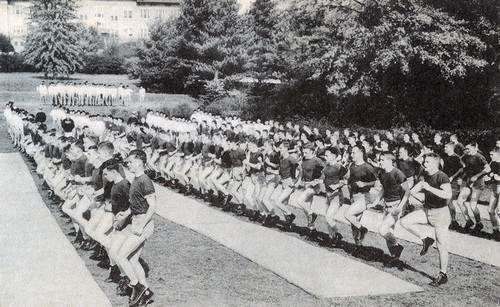

Battalion size ranged from 187 to 400 men, and each battalion would be further divided into 3-4 companies, with each company being further divided into 9-12 platoons. Battalions were generally housed together to promote force unity, and competition between battalions was encouraged, whether in the classroom, out on drill, or on the athletic fields. During the height of training, battalions would arrive every two weeks (this shifted to monthly in 1944). Marching and constant drilling were central to a cadet’s day, and Marine drill instructors had custody of making sure that each cadet was intimately familiar with the fine details of military discipline. This included mastery of the obstacle course constructed at Camp Wilkins. One of the more rigorous training regimens involved the removal of over eleven miles of the abandoned trolley lines of the Athens Railway and Electric Company. All of these endeavors were designed to bring the cadets to a peak of physical fitness.

Athletics were a crucial part of this training, with swimming, track, cross country, and soccer all a part of the core training program. Contact sports such as boxing, wrestling, and ju-jitsu were also part of the training package. There was competition in basketball with other military teams, but the primary sports competition was football. Head Coach Paul “Bear” Wolf (of UNC) and his staff led the Skycrackers to a 7-1-1 season in the first year (1942), but after that season, it was determined that only non-professional cadets could play, and so the 1943 season, helmed by Rex Enright (U South Carolina) had a different standard to meet. Meet it they did, winning five of their six games. In 1944, the competition was even more fierce for Raymond “Ducky” Pond (Yale), and they managed only four victories out of the nine games they played. The football program was nevertheless one of the most successful public interfaces with the Pre-Flight School in Athens, and it spoke well of Commandant Smith’s training program.

There were many challenges to running the Navy program side-by-side with the regular University operations, and frequently, the man called upon to smooth ruffled feathers was Dean of Men William Tate. Whether it was confusion over who had priority in facility usage, or an issue of intrusive noisemaking at inappropriate times, or even the old reliable frictions surrounding the issue of fraternization, there were generally ways found to remind everyone that the greater sacrifices of wartime were in play.

The problems were offset by substantial improvements to infrastructure that accompanied the Navy presence. Roadways were upgraded or newly constructed, several buildings were added to the landscape, and the Athens Airport received substantial gains to their service facilities and an extension of 1,000 feet to the main runway.

Ultimately, the Athens school would be the first of the original four pre-flight programs to cease operations. The final station dinner and party was held on September 21, 1945, and the Athens program was at an end. Those cadets with training still to do marched up College Avenue to board Seaboard Air Lines trains which would take them to Iowa City to complete their training.

In the end, some 18,000 cadets passed through the 12-week training program of the Navy Pre-Flight School in Athens. Both Athens and the University were changed by the program, as were many of the cadets who passed through. Though there was a wide diversity of memories captured by these young aviators-to-be, perhaps the best quote capturing the experience came from a cadet who spent time in Athens, and who would go on to considerable fame in another line of work. A young Ed McMahon may have been speaking for most of the cadets when he observed: “I would not go through Pre-Flight School again for a million dollars, but I would not trade the experience for ten million.”

Those interested in learning more about the Athens Navy Pre-Flight School are directed here: “Tomorrow We Fly”: A History of the United States Navy Pre-Flight School on the Campus of the University of Georgia, Athens, Georgia, by H. Michael Gelfand (1994)