Ending Athletics Segregation in the SEC and at UGA

Desegregating College Athletics in the South

The admission of Black students into colleges and universities across the once strictly segregated South raised the question of when Black athletes would begin to take part in collegiate athletics. The process of integrating Black students into athletic programs in the South was both slow and haphazard, with each state and each school taking its own approach to the issue.

The Southeastern Conference, which was, and still is, the dominant athletic conference in the South, provided no overall guidance to its member institutions on the subject of integration. This was partly due to the difficulties in providing guidance to schools facing differing political obstacles to integration in their own states, as well as the cultural differences between conference schools in the Deep South versus those schools bordering Northern states. In recent experience athletic conferences have coordinated for their member institutions responses to large-scale challenges such as the COVID-19 crisis in 2020, but this practice was unheard of in the 1960s. Athletic conferences such as the SEC maintained academic standards for their member institutions, along with rules, scheduling, and travel guidelines -- and rarely interfered in matters within their member institutions beyond those issues.

The first Black athlete to play for an SEC school was Tulane baseball player Stephen Martin in 1966. Martin’s groundbreaking participation is oftentimes overlooked due to the lack of publicity given to collegiate baseball at the time and because 1966 was Tulane’s last year in the SEC.

Martin not only broke ground in terms of Black participation in the SEC, but he also set a pattern for desegregation that would be followed by most Southern schools: one or two Black athletes would join a team that mattered less to its school to test the response from students and alumni, then the more popular and profitable programs at that school would be integrated. For example, Henry Harris was the first Black athlete at Auburn when he integrated the basketball team in 1968. After Harris spent a year as the only Black athlete on campus at Auburn, James Owens was recruited to desegregate the football team. At Kentucky, where basketball reigned supreme, Greg Page (who died after a tragic practice accident) and Nate Northington desegregated the football team in 1966, long before Tom Payne desegregated the basketball team in 1969. Many of the first Black athletes in the South suffered verbal abuse from fans and, occasionally, opposing players, especially when traveling to venues in cities that were openly hostile to integration. Little was done officially to shield them from this abusive behavior, though their own teammates or coaches would attempt to assist as possible. Black players would also oftentimes be unable to eat in the same restaurants or stay in the same hotels as their White teammates. In addition, with few Black students enrolled in predominantly White Southern universities, Black athletes found few if any social opportunities on their campuses.

Desegregating Athletics at the University of Georgia

At the University of Georgia in December 1963, newly hired athletic director Joel Eaves replaced head football coach Johnny Griffin with thirty-two-year-old Vince Dooley. Dooley, who had served as an officer in the Marine Corps after his All-American career at quarterback at Auburn University, was tasked with rebuilding a lackluster football program coming off of three consecutive losing seasons; a scandal involving the accusations of game fixing on the part of former athletic director (and former head football coach) Wally Butts and Alabama’s head football coach ‘Bear’ Bryant; a losing streak to archrival Georgia Tech; and an apathetic fan base which had long since stopped filling Sanford Stadium’s bleachers.

Dooley was not a stranger to integration. He had commanded an integrated unit in the Marine Corps and had played on an integrated All-Star team after his senior year at Auburn. Dooley was, along with Tennessee coach Doug Dickey, part of a new generation of coaches who came into the SEC during the 1960s and 1970s; these coaches had come of age after World War II and were generally more open to integration than many of their older peers.

In the spring of 1966, Ken Dious, a 6’2”, 185lb. freshman, walked onto the football team during spring practice, playing the End position on offense and defense. In walking on, Dious became the first Black athlete to participate in athletics at UGA. When asked about Dious' participation, Coach Dooley stated that, "[Dious] has the same right to come out for football as any other boy." Though he did not pursue football, Dious opened the door for other Black athletes to wear the red and black uniform of the Bulldogs.

The next year, walk-on James Hurley practiced with the Bulldogs football team during the fall and won a spot on the freshman team, as NCAA rules at the time barred freshmen from participating in Varsity competition. Hurley, who played defensive end, was unable to secure a scholarship position on the Varsity team, so he transferred to Vanderbilt University where he became one of the that school’s their first Black football players.

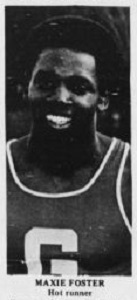

Maxie Foster, of Athens, signed a partial scholarship in 1968 to run track. Some collegiate sports with small rosters did not then, nor do they now, offer full athletic scholarships to each player. Foster was the first Black athlete to sign any kind of scholarship offer at Georgia. Foster had also integrated the athletics programs at previously all-White Athens High School. He was inducted into the Athens Athletic Hall of Fame in 2004.

Ronnie Hogue, of Washington, D.C., became the first Black athlete to sign a full athletic scholarship at Georgia when he signed to play for Coach Ken Rosemond’s basketball team in 1969. Rosemond, who had been an assistant for Dean Smith at the University of North Carolina, looked to build his roster in part with players from major urban centers in the Northeast. In an interview in 2020, former team manager Dave Muia said of Hogue's struggles in being one of the few Black players in the SEC, "I think when Ronnie would go to a place and get called names, I think it made him play even harder. I think he just wanted to just shut them up, and the best way to do that was to play the game he enjoyed the most."

February of 1970 saw fullback John King from Toney, Alabama sign a grant-in-aid with the Bulldogs football team. This prevented other SEC schools from recruiting King, but was non-binding outside the conference. The University of Minnesota Golden Gophers had recruited King as he was coming out of high school and continued to do so even after he signed with Georgia. As Coach Dooley explained in an interview in 1991, the Gophers, like other teams from the North, “were coming South and were doing a good job of recruiting Black athletes.” They signed King to a nationally binding letter-of-intent in late-spring of 1970. Dooley attempted to get Minnesota to release King from that letter, but was refused. King went on to play at Minnesota and was the second leading rusher in the Big 10 conference in 1972, ahead of future two-time Heisman Trophy winner Archie Griffin.

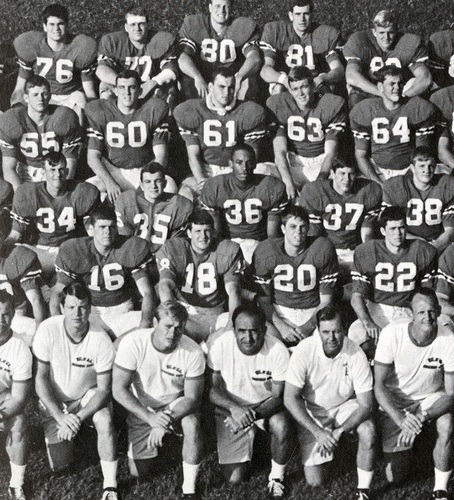

In December of that year, Dooley finally was able to sign players who would successfully integrate the varsity football team. Richard Appleby, Horace King, and Clarence Pope of Athens, along with Chuck Kinnebrew of Rome and Larry West of Albany, would, after their NCAA mandated freshman year on the junior varsity team, become the first Black players to play football for the University of Georgia.

Challenges in Transition

The transition from a fully segregated team to an integrated one was not without its challenges. There were few Black students on campus and social opportunities on campus were limited -- and social opportunities away from campus in the city of Athens were even more limited.

In addition, old traditions of the Georgia football team clashed with the new era of integration. Clarence Pope recalled in a 2007 interview with the Red and Black:

When we got there on our first day of arrival, there were guys that were sitting at the front of the steps at McWhorter Hall [the campus athletic dorm], and you had a Grand Dragon who had a sheet over his head sitting in a chair with a shotgun. You had other guys sitting with shotguns and a banderole belt with ammunition in it. From what I hear, this was a welcome that they always did. It was something we didn’t like.

Despite this, Pope continued:

We knew we going into this we would face adversity, but we considered ourselves as teammates. There might have been or two that had certain rejection [of integration], but as far as the entire team, we drew closer and closer through cohesiveness and understanding.

Coach Dooley admitted in a 1991 interview that, “we had some White players that did not accept the Black players, and it did cause some problems.” To help rectify the problems, Dooley called a team meeting to allow his players the opportunity to speak freely about any racial concernsDooley stated in that interview that, “when we broke these accusations down for the most part it was a matter of perception and once we got the players communicating…it was a big help to us."

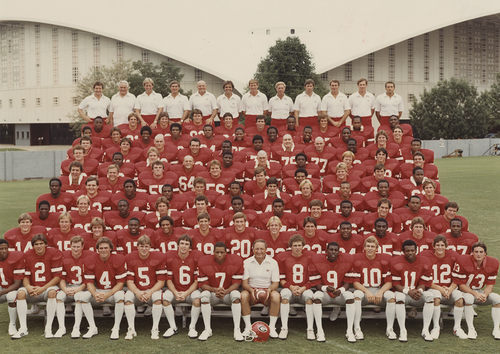

After the 1970s

Though the integration of the Bulldogs encountered a few problems at the outset, the recruitment of Black players into the program continued unabated. By 1980, when the Bulldogs won the national championship in football, almost fifty percent of the athletes on the team were Black, including star players Nat Hudson, Lindsay Scott, Nate Taylor, Eddie ‘Meat Cleaver’ Weaver, and All-American freshman running back Herschel Walker.

Today Black student-athletes at UGA make up the majority of the football, basketball, and track teams, while representation in other sports, including tennis, golf, and swim & dive, lags behind. Black athletes Keturah Orji (track & field) and Teresa Edwards (basketball) are among the most decorated and acclaimed athletes in their respective sports and have both represented the United States in Olympic competition. Even though Black athletes have found success on the field, there is still progress to be made in hiring Black coaches and administrators, especially for those sports where the majority of student-athletes are Black or non-white.