The Georgia Tech-Pittsburgh Sugar Bowl Controversy

"Now the shameful events apparently have ended, but not before irreparable damage has been done to the reputation of the state and its two leading educational institutions in the eyes of the rest of the nation."

- Red and Black editorial, December 8, 1955

Gentleman's Agreement

Integrated games involving Southern schools were rare before World War II. Even for those Northern or Western schools that were integrated, games against teams from the South remained segregated due to an unwritten “gentleman’s agreement”, an informal understanding that segregated Southern teams would not play integrated games in any sport. Regardless of where games were scheduled to be played, integrated teams would leave Black players off game day rosters in order to comply with the segregationist policies of Southern schools.

This agreement eroded quickly after World War II in response to pressure from returning veterans concerned that they had fought ideologies founded on theories of racial superiority abroad only to have segregationist policies remain in place in parts of the United States. The agreement also broke down as more and more Black athletes took their places on Northern and Western college teams and coaches began to refuse to play with only partial rosters. By the 1950s, Southern schools adjusted to the demise of the "gentleman's agreement" by not scheduling intersectional matchups against integrated teams and by declining invitations to post-season tournaments where they could be forced to play integrated teams

Integrating the Sugar Bowl

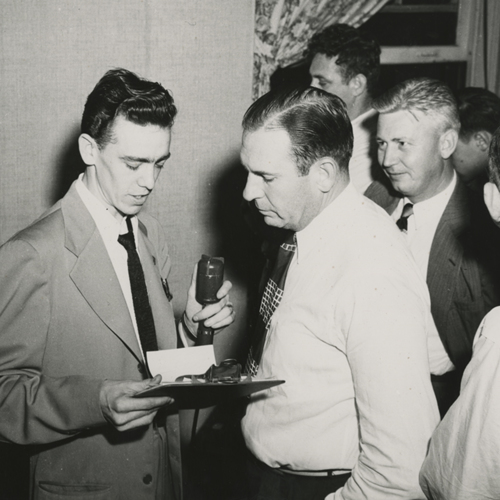

Georgia Tech's football team, ranked No. 3 in the nation at the end of the 1955 season, received an invitation to play in the Sugar Bowl in New Orleans on January 2, 1956. Their opponent was the Pittsburgh Panthers, who would bring a 7-4 won-loss record and a No. 11 ranking to the contest. Pittsburgh would also bring fullback Bobby Grier, the lone Black player on their team.

The Sugar Bowl committee may have been unaware that Grier was a starting player for the Panthers, as he played sparingly in the one Panthers game they had seen in person. The committee did not rescind Pittsburgh's invitation when they learned that Grier was a starting player for the Panthers, even though no Sugar Bowl game had featured an integrated team. The Sugar Bowl committee agreed to not segregate seating in the section set aside for Panthers fans, despite Tulane Stadium, where the Sugar Bowl was then held, having been segregated for all other sporting events.

Gov. Marvin Griffin's Stance

After the match-up was set, Georgia Tech President Blake Van Leer reached out to Georgia's governor Marvin Griffin to make certain that Tech would be able to participate without any political interference. After privately reassuring Van Leer that there would be no interference, Griffin, pressured by pro-segregation constituents, took a starkly different public stance and issued a statement decrying the integrated game:

"The South stands at Armageddon. The battle is joined. We cannot make the slightest concession to the enemy in the dark and lamentable hour of struggle. There is no more difference in compromising integrity of race on the playing field than in doing so in the classrooms. One break in the dike and the relentless enemy will rush in and destroy us."

The response from Georgia Tech and Pittsburgh was swift. Pittsburgh’s acting Chancellor, Charles Nutting, was succinct in his response: “No Grier, no game”. Tech President Blake Van Leer, who had opened Tech to female students, threatened to resign if Governor Griffin blocked their participation in the game, stating, “Either we’re going to the Sugar Bowl or you can find yourself another damn president of Georgia Tech”.

Georgia Tech’s students took their opposition to the Governor to the streets of downtown Atlanta, protesting at the Georgia state capitol building and the Governor’s mansion.

A crowd of around 1,500 University of Georgia students showed solidarity with their archrival by protesting at the Arch, the traditional entrance to the UGA campus. Some students carried signs bearing the slogan “For Once, We're for Tech”. The Red & Black, Georgia’s student newspaper, also carried editorials supporting the position of Tech and expressing their opposition to Governor Griffin; however, some of the editorials also showed their support for continuing segregation as long as it did not interfere with athletics.

The California Eagle, a Black newspaper in Los Angeles, said that it was, "the first time in the recent history of the South that any sizeable segment of white people have uttered a defiance of lily-white politics."

Repercussions

In a show of support for Gov. Griffin, Georgia’s Board of Regents passed a policy restricting Georgia and Georgia Tech to participating only in segregated athletics contests in the future, though this policy was never enforced. Georgia played an integrated Missouri team in the Orange Bowl at the conclusion of the 1959 season with no controversy and without interference from the Regents.

Georgia Tech and Pittsburgh finally met in New Orleans on January 2, 1956 in order to settle the actual athletic contest. Tech defeated Pittsburgh 7-0.