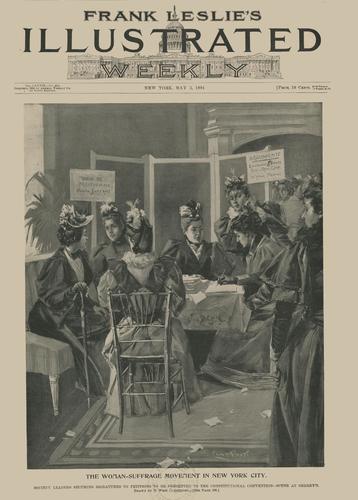

Assembling for Suffrage

The story of women’s suffrage is one of both communal strength and communal fracture. Women across race and class shared the common goal of suffrage, but social tensions and racial prejudices within American society stopped a fully united front. Women’s clubs, meetings, and even parades were, more often than not, racially segregated.

Women in the United States had long been organizing for the sake of women’s rights and community welfare, but a more official women’s club movement began during the Progressive era in the late 1800s. Though racially segregated, both white and African American women’s clubs were involved in improving education, securing health care, promoting temperance, and campaigning for social reforms surrounding the juvenile justice system and child labor. African American women’s clubs also fought for racial justice, including to stop lynching and the convict lease system in the South.

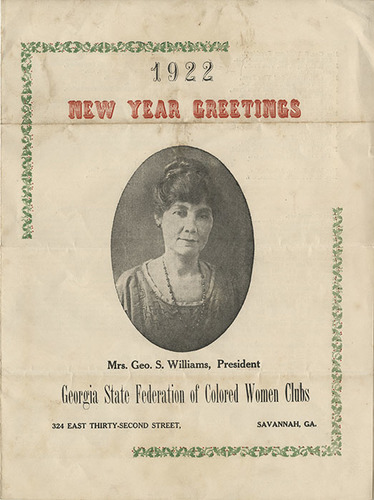

Mrs. George S. Williams, also known as Mamie, served as president of the Georgia State Federation of Colored Women Clubs. In 1924 she represented Georgia as the first African American woman appointed to the Republican National Committee. She was also the first woman to speak on the floor of the National Republican Convention. This leaflet details this club's goals for the coming year, including registering women and men to vote, securing health care, and developing asylums for people of color.