From Georgia to California (and Back Again)

The late 1830s and 1840s were the most productive era of Georgia mining; however, Georgia mines lost their luster when word of a new strike reached the East from California. Georgia became another launching point for journeys west. Despite efforts of prominent locals to keep miners at home, prospectors left in an exodus for the Pacific Coast in 1849. Perhaps as many as five thousand Georgia miners departed for California in this initial rush.

By the late 1850s, California’s gold fields had become crowded and large companies dominated the richest lands. Some mining engineers began to consider returning to the old southeastern gold districts with the new technology pioneered in California. To accomplish this, they first had to bring together speculative capital, engineers, and southern landowners.

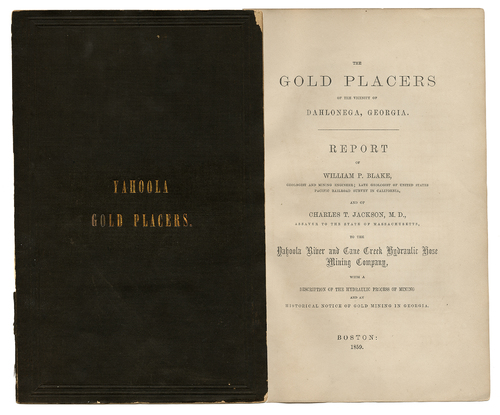

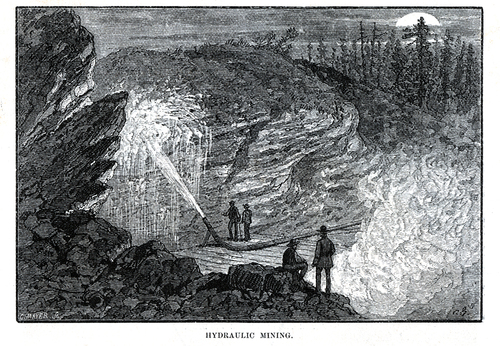

For William Phipps Blake, an engineer operating out of New York City, the future of southern mountain mining lay in hydraulic techniques, he promised “that by introducing water by canals… and washing down the hills by the hydraulic process, a new era of mining will be inaugurated.” Hydraulic mining is a costly and elaborate process using canals, flumes, and high-pressure hoses to wash away huge quantities of mountain soil to expose hitherto hidden gold deposits. This was an opportunity to replicate, or even better, the success of western mining.Blake’s showmanship and professional endorsements helped raise hundreds of thousands, if not millions, of dollars for speculations, including the Yahoola River and Cane Creek Hydraulic Mining Company and the Nacoochee Hydraulic Mining Company.

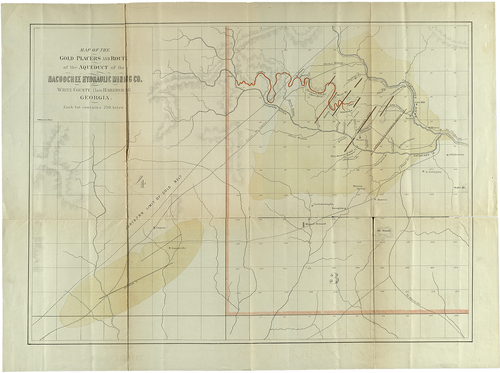

Blake’s work followed a standard template. He would travel south, survey a prospective mine site, and offer some predictions about profitability and how California techniques might be used to great effect. His reports also often included a map or two and sketches of prospective hydraulic canals. Blake’s report was then published in pamphlet form in the Northeast, where it was used to drum up capital for the mining operations.

Hydraulic mining was expensive, but the work of experts like Blake, coupled with northern investment capital, brought the California model to Appalachia by the start of the Civil War. The most significant concentrations of hydraulic mining centered on the gold-rich watersheds of Georgia’s Chestatee and Yahoola Rivers and Cane Creek, where the first hose pipes came online in 1858.

The technology of hydraulic mining recaptured the frenetic speculative spirit of the early 1830s, creating a brief second gold rush in Appalachia. Georgia miners undertook the extraction of natural resources on an industrial scale. Their efforts drew parts of the southern mountains, at least temporarily, fully into the national mineral economy in ways that presaged the timber and coal booms of the postbellum period. Gold mining would gradually cease to be an important economic force in Appalachia (hydraulic mining would ultimately fail to resurrect the dynamism of the early Georgia gold rush) but miners were there to stay.