Cherokee Removal

The state of Georgia moved quickly to secure the interests of American miners. In 1830, the legislature declared its control of all Cherokee territory within Georgia’s boundaries, and Congress passed the Indian Removal Act (which promised to force all Native Americans from the state). This violated the Treaty of Hopewell, signed in 1785, which had defined the borders of the Cherokee Nation and ensured that non-Native citizens of the United States could not settle within the Cherokee boundaries. Two U.S. Supreme Court cases, Cherokee Nation v. Georgia (1831) and Worcester v. Georgia (1832), interceded on behalf of the Cherokee Nation as a sovereign nation within the boundaries of Georgia. However, President Andrew Jackson, continued to encourage the removal of Native peoples to west of the Mississippi.

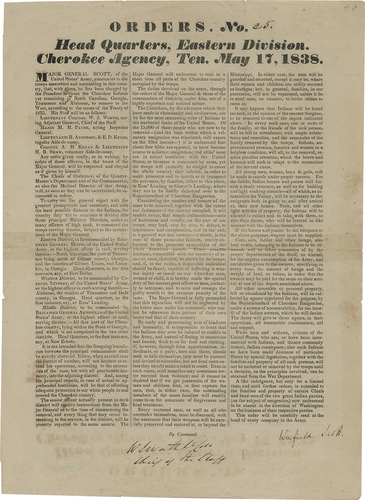

In 1835 the Treaty of New Echota, signed without the authority of Principal Chief John Ross or the Cherokee government, required the Cherokee Nation to exchange its lands for a parcel in the "Indian Territory.” Beginning in 1838, President Martin Van Buren ordered the Cherokee to be removed, the forced march became known as the Trail of Tears where thousands of Cherokee perished due to lack of food, disease, and exposure to extreme temperatures.

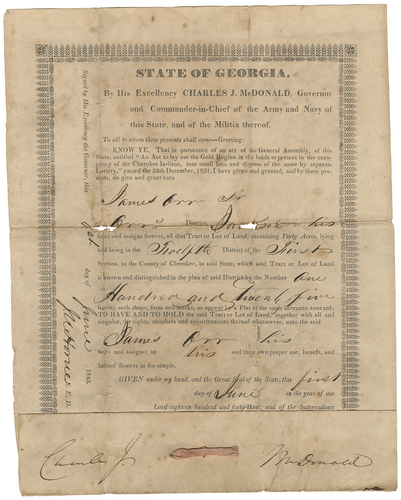

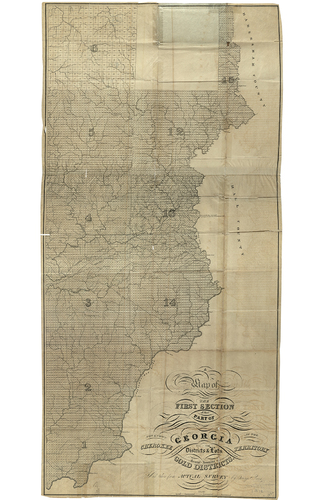

State officials began auctioning off Indian land in 1830; white Georgians could claim Cherokee territory in 160-acre agricultural lots and 40-acre mining tracts within the gold belt. Only U.S. citizens, residing in Georgia for 3-years, and meeting these criteria, bachelors over 18 years old, widows, orphans, and married men, were eligible to register for the draw. No people of color, including free Blacks could participate in the lottery.

The initial gold lot draws stirred up an incredible speculative fever. A single county’s land lottery drew twelve thousand interested Georgians; in total, 133,000 state residents registered for thirty-five thousand available gold lots. Investors hovered around the margins of the drawing day crowds as the wooden lottery drums spun and officials called out the names of winners one-by-one, waiting to make offers to the lucky citizens who won the most promising gold lots. Land changed hands almost too quickly for courts to follow, and the region was rife with hucksters, confidence men, and downright frauds intent on making their own profits from gold fever.

The Federal Union (Milledgeville, Ga.) published the prizes drawn in the land and gold lotteries listed by the date of the lottery and county of residence of the winner.