Environmental Impacts of Hydraulic Mining

Whatever people thought of the relative sophistication of gold operations, they consistently acknowledged the steep environmental costs. According to a correspondent to Merchants’ Magazine,

“on approaching Dahlonega I noticed that the water-coarses [sic] had all been mutilated with the spade and pickaxe, and that their waters were of a deep yellow; and having explored the country since then, I find that such is the condition of all streams within a circuit of many miles. Large brooks (and even an occasional river) have been turned into a new channel, and thereby deprived of their original beauty. And of all the hills in the vicinity of Dahlonega which I have visited, I have not yet seen one which is not actually riddled with shafts and tunnels.”

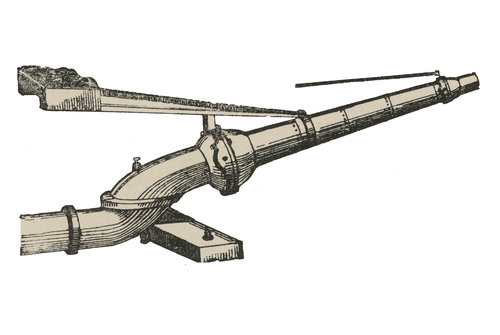

Hydraulic mining techniques found their way to Georgia and revived the state’s gold economy, but at a cost. Hoses blasting jets of water against hillsides unveiled more southern mountain gold, but at the expense of the mountains and valleys themselves. The power of water harnessed by these new techniques was difficult to convey, but Blake described the work succinctly:

“The water issuing in a continuous stream, with great force, from a large hose-pipe, like that of a fire engine, is directed against the base of a bank of earth and gravel, and tears it away. The bank is rapidly undermined, the gravel is loosened and violently rolled together, and cleansed from any adhering particles of gold, while the fine sand and clay are carried off in the water . . . Square acres of earth on the hillsides may thus be swept away into the hollows, without the aid of a pick or shovel in excavating.”

Blake promised prospective investors that Appalachian nature all but demanded hydraulic mining, for “the topographical features are more favorable than in the other gold-producing districts of this country, the water being more abundant with a greater power of fall.” Even an environmental quality local farmers had long considered detrimental, soils prone to easy erosion, was cast as a stroke of luck for hydraulic miners. Blake well understood the hazards of the methods he advocated—he had, after all, worked in California, where the environmental and social costs of hillside washing were too obvious to ignore. But whether out of a desire for personal profit or a genuine belief that the benefits outweighed their costs, he brushed aside these worries in his plans for Georgia. Entire mountainsides that had been washed away had to come to an eventual rest somewhere, but fortunately for mining companies “the descent or fall of the stream[s] [was] sufficiently rapid to carry off the tailings.” The gold would remain and the debris became someone else’s problem.