Life in the Gold Region

In 1849, a correspondent for Knickerbocker magazine described Appalachian miners as unkempt, ignorant, and uncivilized. And in Dahlonega, a scene of frenzied economic opportunity, life remained rough, lived out in unpainted log houses.

The southern writer William Gilmore Simms highlighted the state’s rough nature and rough people in his 1834 novel of the gold district, Guy Rivers: A Tale of Georgia. Although he likely never visited the gold fields in person, he opens the novel with a memorable criticism of the north Georgia landscape, a place “if not absolutely desolate, [it] has, at least, a dreary and melancholy expression, which can not fail to elicit, in the bosom of the most indifferent spectator, a feeling of gravity and even gloom.”

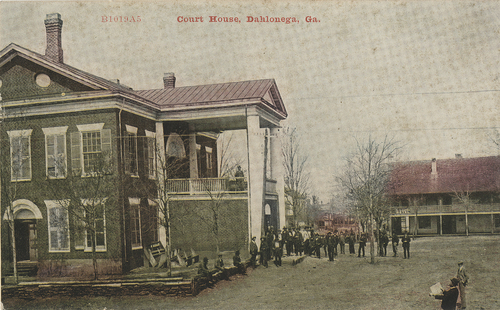

The town of Auraria sprang-up in 1832 quickly growing to a population of 1,000 as announcements of the gold finds were published in national magazines. Only a year later Auraria dwindled as Dahlonega was named the Lumpkin County seat. By 1834, a number of houses were built in Dahlonega, the courthouse was completed two years later, and by 1900 the city’s population exceeded 1,200.

The year that the U.S. Branch Mint opened in Dahlonega, 1838, the General Assembly of the State of Georgia passed an act to extend the town's corporate limits.

Since mining tools and machinery were expensive many landowners supported mining operations through surplus agricultural labor. Most crucial was slave labor, which appeared early and often in the gold district as planters from the piedmont and low country turned to mining during the winter, when cotton work was slack. Slave leasing was also popular. In this fashion, Georgia gold mining served as a supplement to, rather than a competitor for, the state’s cotton plantations.

A few free Black people also labored in the mines, and at least one Black man, James Boisclair, purchased his own plot of land despite a Georgia law prohibiting the sale of gold lots to African Americans.